By Carl Valle

Figure 1: The Australian company Kinetic Performance boasts a decade of experience working with the best teams in the world and have committed to updating their software for the demands of North American teams, not just Europe, NZ, and their backyard.

A Numbers Game or Time to Slow Down?

Over Labor Day weekend, a few coaches asked me about the use of barbell velocity tools that are out on the market now. In the early 2000s, Tendo was all the rage and stayed on top until a few years ago when the Australian product Gymaware started to hit North America. Linear Positional Transducers are over 20 years old and are not new to Europe, so why the rise in popularity again now? Besides my articles promoting accurate training, an increase in wanting more data is because training is getting a big wake up call and audit with validation. Last year I read Bryan Mann’s guide to Velocity Based Training (VBT), and it was a nice way to introduce and outline the ins and outs of bar speed. Included in the manual by Mann were personal history, fundamental concepts of barbell speed tracking, but nothing on some of the technology considerations I felt are confusing coaches. His science and practice was a great read, but now people are asking questions on what to do with investing into equipment.

Stepping back from the needs of budgeting, technology requirements, and even workflow, a bigger need is to ask what the purpose of weight lifting is for sports performance? It may sound strange at first, but a big problem in strength and conditioning is that very few coaches can explain how their program improves athlete speed and power with real data. Add in the need for added mass in some sports such as rugby and American football, VBT must demonstrate the clear transfer of explosive power for jumping, sprinting, and adding mass. If you were to ask any football coach what characteristics they want in a player besides skills of their position, size and speed are paramount. When I read blogs about perception of bar speed for bench press like a subjective RPE for velocity, we are now back to the stone age with technology and methodology, and this is frustrating. In this three part series, I will ask and answer the tough questions, keep things very clear and straightforward, and share what some of the best coaches do to use VBT with their athletes.

Getting the body to displace faster or move the bar faster?

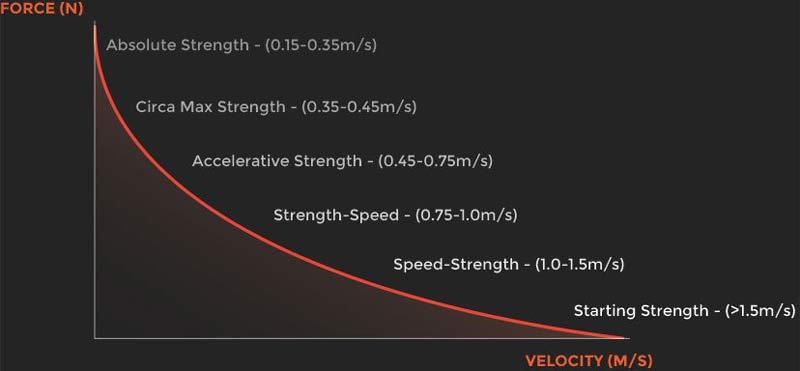

Figure 2: The continuum shared above by Pushstrength.com is popular in some circles, and the convenience of actual velocity parameters is intriguing. A raw speed indicator can be enough to look for fatigue if lifts are not hitting precise thresholds and coaches can use small drop-offs of .2-.3 meters per second for exploring the interplay between peripheral and central fatigue. Bench Press and lower body lift discrepancy metrics are starting to show how global and local changes are happening, and soon we can understand how fatigue can be sliced as data is collected with team training. While the middle of the curve is a death valley for me, it is useful for managing recovery periods since the speed strength lifts do help with adaptation identification.

Does moving the barbell faster transfer to moving the body faster in general? Nobody is going to believe that bench pressing faster will result in game breaking speed, and even those that do speed lifting will dominate the 100 meter dash. So why the barbell tracking rage now? Several coaches look at me like I just shared that no Santa Claus exists when I explain the following:

Most athletes care about momentum or their speed relative to size in their sport. Nearly every successful program wants to improve speed and repeated speed, so weight training is only a part of that formula. Since Velocity Based Training is a sub-component of weight training, it’s more important to evaluate the speed of the body versus the speed of the bar.

So should we just throw away our Tendo systems or convert the new Push Strength gauntlets into Batman costumes for our kids for Halloween? No. Velocity Based Training has purpose and value, but always think about what the hierarchy of importance in training. It is no mystery that I am biased that speed is essential to most sports, and I also have the benefit of it being true in the research.

History of Velocity Based Training

Over 100 years ago, during the early stages of sports training, velocity was about how fast one was going, be it a person or many times a horse. The reason I interviewed Bill Pressey and wrote about electronic timing was because some young strength coaches are polluted with the addiction to strength equals speed; in reality the combination of speed training, explosive exercise, and strength work drives the improvement. My first exposure to Velocity Based Training was nearly 20 years ago when reading the work of college coaches from the ASCA World Books. In fact, the cream from the 1970s to now is my reality check of what matters in training, and I review the materials every fall. The two years that I didn’t review the information I got lost in a sea of complexity and lost my bearings, failing to get real improvements and was humbled. What was key? Meters per second was the backbone metric for nearly every speaker. Every chart and every workout eventually were distilled to time and distance, not physiology. My first A in school was in Biology, and my last A in college was kinesiology. I say this because some courses like chemistry and physiology are difficult to apply because they are describing the exchanges internally, but simple math and crude physics trump everything. Physiology describes why something happened performance-wise, but rudimentary physics shows what happened in great precision.

Figure 3: The American company Assess2Perfom gambled on making the sensor attach to the bar for the team and scholastic market. 90% of the needs of coaches are traditional barbell exercises, so this was a smart play, but the consumer market may disrupt things down the road with athlete data syncing. The reality is not all training needs to be measured and tracked, just the key sessions.

Three swimming topics made me rethink how training should be guided. One was the lactate information from the work of the 1980s, the engineering side of technique from Bill Boomer, and the epic strength training panel with Dr. Tom McLaughlin fighting off the Ph.D. guys from Nautilus and Isokinetics Inc. Those three presentations should be the foundation to any coach, not just swim coaches. All three topics were unique, but all of them focused on velocity measurement for performance. What resonated with me was how everything presented connected, meaning how all three subjects and presentations had a common thread of moving a body faster. Fast forward to today and some companies providing GPS tracking are on the right path, sharing peak velocities of athletes, but are still not understanding the core values of speed, and how to connect training to the end result.

Due to the limitations of rule constraints, using tracking options only reveal relative speed and without linear testing the data is in a vacuum. Even linear testing without sport perspective is still limited as well. When absolute speed, sport specific speed, power testing, training benchmarks and programming are connected, can Velocity Based Training for the weight room be useful. A successful weight-training program may not create a successful speed result on the field. Only when the cause and effect of Velocity Based Training shows up on the speed testing, it may have a chance in game situations.

The Differences in Barbell, Ball, and Body Speed

Figure 4: Before you measure a workout you need to plan the training. Coaches have still resorted to Excel because much of the software available stinks. Teambuildr and other companies that are hardware providers such as Push are offering ways to generate, collect, and analyze training data.

When I teach athletes to do Olympic lifts, I progress from what I call a body, ball, and bar sequence in order to maximally train and gradually learn. I realize that better coaches exist and teach the snatch or clean and jerk better than me, but it’s not a race to be better in the weight room; it’s to be better overall more consistently with a large diverse population of athletes. If you can’t move well with just your body, adding a ball complicates things. If you can handle a medicine ball overhead throw properly, you should rethink what you are doing with a heavier and more complicated exercise. What is confusing is that most coaches start with the most complicated. I have no emotional attachment to any lift, and have advocated Olympic lifting to those frightened by not being able to teach them, and removed the use when it was not appropriate. When coaches want to use devices that measure bar speed, the question is what exercises are appropriate, and what do you do differently if you get the information? This is not attacking the use of Velocity Based Training as I am a proponent, but marketing is corrupting the science and practice from “crowdfunding trailers” designed to seduce coaches to bring boring science into video game reality complete with floating charts and dancing numbers. When I see Kickstarter and Indiegogo campaigns using the terms exercise signatures and power while doing push-ups and kettlebell swings I get worried. Force Plates become Farce Plates, and power is now portrayed in a smartphone app, complete with slick rendering from potato chip eating coders in start-up incubators.

The digital dark age has new light though, so don’t despair. Strangely the influx of Crossfit saved the slow death of Olympic style weight training after the HIT plague and functional training only crowd put that information on life support. The Olympic lifts were back in demand, and technology companies saw plenty of new users beyond high schools and college athletes. While medicine ball throws are nice, and speed squats are an option, most coaches like the large amount of high threshold motor units being recruited from weightlifting (Olympic style). Coaches are talking and debating of what does the data mean to on the field results, and now we have better answers with the research and real evidence.

Instead of equating Velocity Based Training to barbell tracking, I think we should focus on the different speeds in training and sports performance. They are the following:

Body Speed – How fast athletes can accelerate, change direction, and maximally displace themselves.

Bar Speed – Metrics of power exercises that create large outputs based on common bilateral exercises.

Ball Speed – Peak velocity of a known training projectile with specific exercises.

Note the similarities and differences with the three speed qualities. Having great body speed may not equate to excellent ball speed, and bar speed is not a magic ticket to running faster. Finally, throwing a medicine ball 18m may not make you the next sub 10 second sprinter, but at least you can now know if the distance was indicative of ability with new technology. Body speed being a premium, the question is how do the other two speed qualities help feed into higher performance?

Does Velocity Based Training Work?

A simple question people are asking is it worth tracking bar speed at all if slow lifts like squats are helping early acceleration, the area that determines so much success in sport. Also, if athletes are doing sprinting are high-velocity lifts worth it? The answer is not a blanket one, since each sport, each program, and each athlete is unique. On the other hand, some universal principles exist, and general guidelines can be tweaked to fit each circumstance.

Back to the 1981 ASCA conference, Dr. McLaughlin pointed out in the study from Stone and Garhammer, a classic principle of weight training. He stated that the intent or effort had to be equated, not just the velocity of the lift. Effort and bar speed are not the same, since an athlete may reach a metric but not feel needed to go beyond it. Submaximal training drives much of the changes, so doing maximal lifting with a slow movement may create better adaptions at specific time periods. High speed doesn’t mean faster athletes, unless the power produced shows up later in testing and transfer of sport activities.

Also, the goals of weight training are not as simple as increasing contractile dynamics of the neuromuscular system, as the Olympic lifts and specific squat protocols are a different beast. For example, the Olympic lifts such as the clean and squat have a rhythm that may be much different than jump squatting in terms of average power and peak power. During early development periods of some athletes time under tension does matter a bit, since you are learning positional awareness and some muscle groups need more exposure times during lifting. A common example is squatting and wanting to pause at the deep bottom position of the lift. Not only is one teaching proper depth, posterior muscle groups are getting excellent activation differently than shallow squatting. Speed concentrically may be a distraction when athletes are learning to lift properly. Teaching is part of the equation and getting bar speed too early is leading down a bad path.

Figure 5: The most important quality besides valid data is the ability to use the product in a group setting if you are coaching teams. Workflow should be the same or better with technology, and any equipment and software user experience that interferes with speed and simplicity needs to be fixed, or adoption is not happening.

Speaking of path, bar path matters as well. The same lessons from chasing total weight numbers in the training facility applies to chasing bar speeds as well. For example one coach bragged about having great clean numbers with his athletes, but their verticals simply didn’t match their weights. Several reasons can explain the poor relationship between weight room numbers to more athletic tests, and Bryan Mann shared that in his manual in great detail. One factor that was not talked about is the bar path needing to be close to the body and have the limbs and axial skeleton be in harmony with the kinematics of the athlete. Too much swinging of the bar recruits muscles inferiorly, and poor jumping can be a result. Also performing the lifts properly is not about how much power one develops in the activity, it’s about how much load they can legally move sport wise, and that may not be better. The Olympic lifts or weight lifts are about total loads, and skills may allow a weaker athlete to achieve a higher success with a heavier load via better timing. Most sports are about being ballistic in nature such as sprinting and throwing. Lifting, unless the exercise has a release or body displacement, usually decelerates bar momentum. The transfer may not be mechanical, but it may be neuromuscular and or general in nature with global adaptations. It is up to the program to decide what is working and why, since no single research study can unlock what is going on in a holistic system.

Some coaches scoff at measuring power at all because sport actions usually are during very narrow time periods, but if you are in the weight room measure what you are doing in it, then one can see if changes are happening elsewhere. Only when you have all of the data can one connect the dots. So it’s better to think about how measuring bar speed can manage power with higher accuracy, versus using a methodology of bar speed to push training practices. At the end of the day, the fastest athletes are not the best because of the metrics of bar speed, and to say that Usain Bolt would run faster from it is a stretch. What is safe to say is that athletes that need a focus on acceleration, a period that overload benefits the most, those looking to get athletes better with weight training may want to investigate Velocity Based Training to all three areas. The interaction of medicine ball training and sport throwing, weight training, and speed workouts generates enough data if done right to know how to refine results and improve a team program. Coaches should know what areas to focus on and what is likely not going to create the “smallest worthwhile change” in training, and pick the right battles with the right data. Bar tracking has three primary best practices, and several coaches have set a standard of what to do for testing and training.

Future Considerations

In closing, the goal of the article was to understand better what the underlying mechanism coaches should focus on is. Tracking barbell or weight training outputs is not new, and for decades this information was already researched. Currently, a lot of interest in barbell and implement tracking is resurfacing because of data being the new oil and technology is more widely available. I think taking a moment to slow down and think about what our true goals are, usually developing athlete momentum, should be the primary responsibility. Athlete’s “Body Speed” is far more important than looking a small percentage of weight training, and coaches should look at how their training is improving sport speed and capacity to repeat it. In the next article, we will investigate the relationships between resistance exercise and improving speed based on the research and available historical data.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

Waiting for the next article indeed! According to my article search, there’s very little studies about weight/power training’s influence on athletic performance. And most of them compare the improvement to movements like; squat jump, CMJ, shot throw, standing long jump, etc., which are far away from solid athletic performances.

One of the best articles I’ve read in a long time. Great topic. Extremely well written, and with a fresh perspective. Got me fired up. Thank you for making it available . For the record I reached your work via Kevin Neeld’s website.

-Jason

Nice article Carl. Can you please tell me where can one get Dr. Tom McLaughlin strength training material that you mentioned in the article.

Thank you

Jure

Fantastic Article Carl – you are exactly the person I am looking for! I am an NYU student founding a startup in the field. We got a great team and we are in the finals of several startup competitions. I would love to talk and explore and advisor/mentorship opportunity which can be mutually beneficial. Please let me know what you think!