By Ken Jakalski

No other issue regarding technique and mechanics for enhancing speed remains as controversial as the contribution of arm swing to faster sprinting. Even the world’s top coaches and researchers have different opinions on this issue.

Dr. Ralph Mann notes the following: “Contrary to popular belief, superior arm action does not produce superior sprint performance. In fact, regardless of the quality of the sprinter, there is no significant difference in the arm action. If a sprinter could improve the horizontal velocity simply by moving the arms faster, then even old, out of shape coaches could run as fast as the elite sprinter since virtually everyone can move their arms fast enough to produce an elite level stride rate of five steps per seconds.”

In his Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling (2010 Edition). The following line is underlined and in bold. “Thus, it is the legs, not the arms, that primarily dictate success in sprinting.”

He believes that whatever motion demands that are made upon the arms—like those in sprinting– can easily be produced.

However, Mann qualifies his position by noting that this doesn’t mean arms aren’t important in sprinting. “They are critical to the maintenance of balance,” he says, “as well as providing a slight vertical lift during each stride.

Frans Bosh, the author of the highly detailed and comprehensive book: Running: Biomechanics and Exercise Physiology Applied in Practice, has a different view.

“Clearly,” he says, “the action of the arms has a greater function during running than merely maintaining balance or compensating for the small disturbances in body posture.”

Bosch feels that one of the ways the arms contribute to the amount of speed that a runner can develop is by “increasing thrust in the direction of progression.”

However, he also says the following: “When running at speed, the upper body is held erect. As a result, the forward force provides by one arm to support push-off is just as great as the counteractive force moving the other arm in the opposite direction. The net result in the forward direction is equal to zero. There is no direct contribution to forward thrust during speed running.”

Legendary coach Charlie Francis remained a firm believer in the significance of arm mechanics to sprinting. “The arms can control the legs,” he noted, “when things are going right.”

But Francis offers his own caveat. “It should be noted that, while arms are extremely important in sprinting, and can help create the fluid, relaxed but powerful stride that every sprinter strives for, even the greatest arm mechanics will be of little use when leg mechanics are neglected.”

In an interview with Jimson Lee for Speed Endurance, Dr. Peter Weyand noted the following when asked about the importance of arm swinging in sprinting.

“Once a runner is up to speed, the arms swing largely like passive pendulums, providing balance, minimizing center of mass energy losses and conserving the body’s momentum. While arm movements are coordinated with torso and leg movements to achieve the energy transfers that minimize center of mass energy losses, they certainly do not control leg movements and have very little effect on the all-important ground reaction forces.

Dr. Ken Clark of West Chester University tends to agree with both Mann and Weyand.

“Once the runner is up to top speed, the arms mostly serve to counter-balance the legs and have minimal effect on setting the tone for stride rate or length. While I don’t have an issue with incorporating a few basic arm drive drills into the early portion of practice, I have not had success either as an athlete or coach by making arm action a big area of technical focus.”

Clark does look at upper body action (torso rotation, arm swing) as an indicator for issues with the legs. Since the arms are synched up with and counterbalance the legs, if there is excessive rotation or lack of a range of motion with one arm, it may indicate an issue with the motion of the opposite hip or leg that needs to be addressed.

And what is my contribution to this debate? Watch the following clip of World Paralympic sprint champion Tony Volpentest. Nineteen years ago, Volpentest ran on my high school track, clocking an amazing 22.94–without having feet or lower arms. As a result of that experience, coupled with what I learned during a visit to the Harvard Locomotion Lab in 2001, I drew the following conclusion about arm swing.

Video 1. Paralympic sprinter Tony Volpentest at the 200 meter finish.

“Arm swing is often unique to the body segment lengths, the location of muscle attachments and hard-wiring of each athlete, and arms, in general, perform like passive pendulums, providing balance and minimizing any center of mass energy losses. Arm swing does not control leg movement, and neither the amplitude nor direction of arm swing appears to contribute to force on the ground.”

So, is this one of those “load six issues,” something coaches should focus on if their “insides tells them too”?

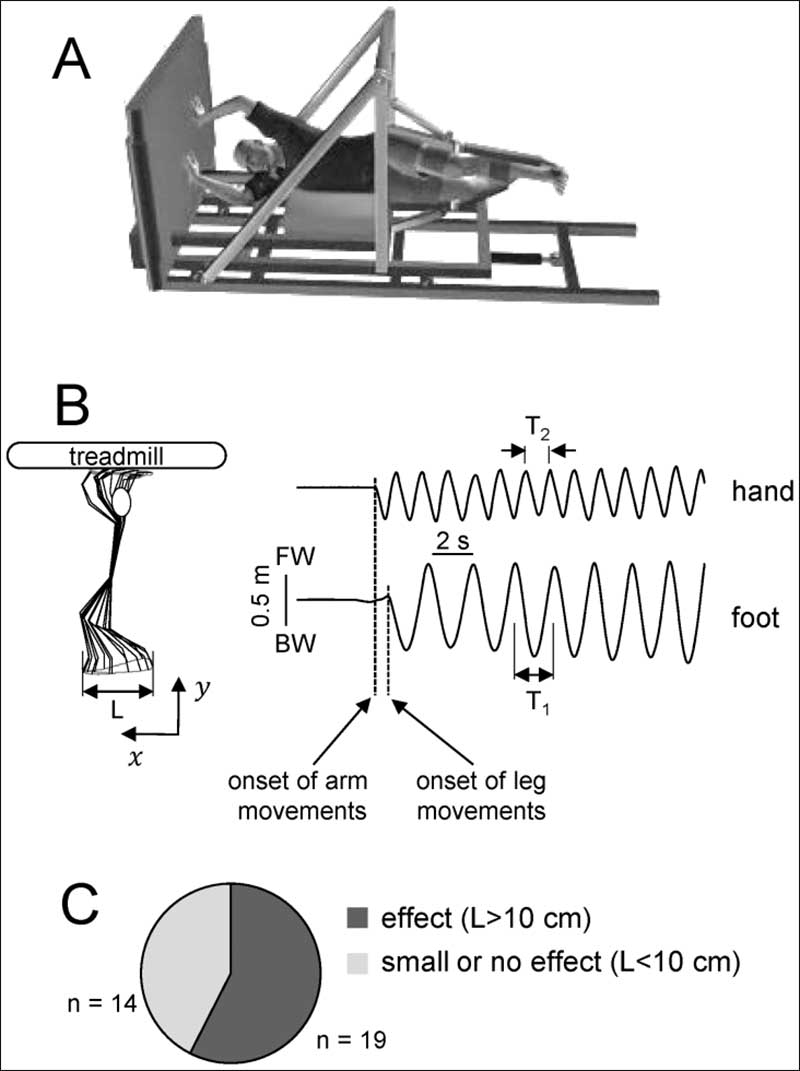

A 2014 study, “Locomotor-Like Leg Movements Evoked by Rhythmic Arm Movements in Humans,” struck me as yet another unique take on the arm swing issue, at least on the basis of the findings of their rather unusual research project. As the authors note: “We found that moving the arms rhythmically on an overhead treadmill, as in hand-walking, often elicited automatic, alternating movements of the legs in a significant proportion of tested subjects as in normal walking, the frequency of leg movements increased with increasing frequency of arm movements during hand-walking.”

Their conclusion: “The bulk of the evidence, therefore, points to a predominantly active (neural) rather than passive (mechanical) nature of the leg movements evoked by hand-walking.”

This was, to say the least, an unusual experimental set-up. Subjects lay on their right side with each leg suspended in what they described as an exoskeleton. The subjects’ arms were free to move, even the lower arm, by way of a small pillow placed on a belt.

Figure 1.

So what were the participants asked to do?

They were instructed to “reach overhead to the treadmill and rhythmically displace their hands on the shifting belt of the treadmill as if they walked on the hands.”

And once the horizontal treadmill started up, what happened?

Leg movements were systematically elicited by those unusual “walking arm” movements. And these leg movements showed some similarities to those of voluntary air-stepping and upright locomotion.”

Does this then support the position–held my many– that fast moving arms make for fast moving legs?

Not necessarily. My first thought was that these findings reflect our evolution from four-legged locomotion. And the authors do mention that, human bipedalism is often thought to have evolved from a quadrupedal precursor. “One of the distinctive aspects of primate quadrupedal walking,” they note, “is the use of diagonal couplets of interlimb timing.”

Though the study does reinforce the idea that humans reveal a neural coupling between arm and leg movements, the researchers point out that the frequency of these leg movements tended to be lower than that of arm movements.

So what is going on?

What we may be seeing in an example of Central Pattern Generators, biological neural networks that produce rhythmic patterned outputs without sensory feedback. CPGs have been shown to produce rhythmic outputs resembling normal “rhythmic motor pattern production” even in isolation from the motor and sensory feedback from limbs and other muscle targets.”

Dr. Ken Clark suspects that the arms and legs are always linked from a timing and amplitude standpoint via these CPGs, but believes that notion of one exerting control over the other, as in the speed of the arms influencing the speed of the legs, is not possible.

Does this mean a farewell to the significance of arms in sprinting?

I don’t believe so.

Dr. Clark acknowledges that arm cues may be valuable when leg cues aren’t working for particular athletes. “Although it is the legs that transmit force to the ground and the ground reaction forces that ultimately affect the center of mass,” says Clark, “if leg or posture cues are not working, potentially arm cues could help an athlete’s leg technique.”

Many coaches contend that concentrating on the arm swing helps sprinters maintain good mechanics, especially during late stages of races where mechanics begin to break down. In that regard, why feel guilty about employing a training strategy that others might find unnecessary?

One of the great quotes from Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms may be the best advice for coaches who value arm swing mechanics.

“You don’t have to pretend you love me.”

Please share so others may benefit.

[mashshare]References

- Bosch, Frans. Running: Running Biomechanics and Exercise Physiology Applied in Practice Fans Bosch and Ronald Klomp. N.p.: Elsevier, 2005. Print.

- Francis, Charlie. Key Concepts: Elite Series. N.p.: n.p., 2008. Web. 2008.

- “Interview with Peter Weyand.” Interview by Peter Weyand. Jimson Lee, n.d. Web.

- Mann, Ralph. The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling. Place of Publication Not Identified: CreateSpace, 2011. Print.

- Mann R, Sprague P. (1980) A kinetic analysis of the ground leg during sprint running. Res Q Exerc Sport. 51(2):334-48.

- Sylos-Labini, Francesca, Yuri P. Ivanenko, Michael J. Maclellan, Germana Cappellini, Richard E. Poppele, and Francesco Lacquaniti. “Locomotor-Like Leg Movements Evoked by Rhythmic Arm Movements in Humans.” PLoS ONE 9.3 (2014): n. pag. Print.

Great insight, Ken,

Thanks for keeping us informed. You presented well thought arguments substantiated by science and reason…

I would love to hear your response on my situation as a sprinter. In the start and acceleration phase, when concentrating on fast arms my leg cadence matches my arms BUT that overall cadence is much SLOWER than if I concentrate on leg speed and just Allow the arms to swing. My cadence is much faster with this legs first approach and the arms feel as though they Follow the legs. This is contrary to everything I was taught. I am not sure if this is more common than believed or is this perhaps just a wiring abnormality in my body. Also I am wondering if the arms debate is correct but only up to a certain speed not accounting for maximum efforts..I was a sub 11 sprinter in college..