By Ellie Kulick and Dr. Rebecca Shultz Ph.D., Lumo Bodytech

As runners, we’re often looking for ways to improve our pace, our mileage, and our form. It’s a constant battle between reaching our goals and avoiding injury that would restrict our training for weeks, or maybe even months.

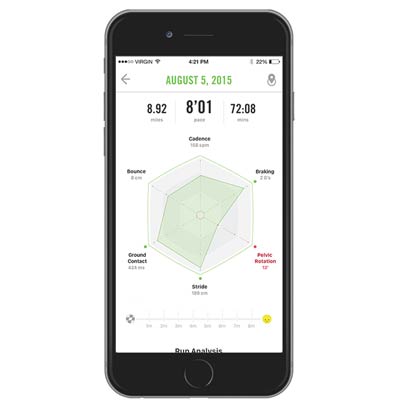

If this resonates with you, I’d like to introduce you to Lumo Run: a recently launched pair of smart running shorts by Lumo Bodytech that helps runners improve performance as well as decrease the risk of injury through capturing and measuring key running biomechanics to provide actionable feedback during and after every run.

Video 1. Overview of the Lumo Run wearable sensor.

To fully understand the benefits Lumo Run brings to your everyday run, it’s crucial to understand the role biomechanics play in helping you become a better runner.

Running Biomechanics

Running biomechanics refers to the mechanical laws relating to movement and structure of our bodies when running. In other words, it looks at how we run through focusing on aspects like how our muscles and joints function while running. These include familiar terms like foot strike patterns, pelvic movements, ground contact time, stride length, and others; it is essentially a deep-dive analysis of your running form.

Out of more than 15 biomechanical measures that the Lumo Run can capture, six metrics have been identified to most significantly affect your running form. Lumo has worked with leading running research institutions, such as the team lead by Dr. Jonathan Folland of Loughborough University (UK) and Dr. Rebecca Shultz Ph.D., who has dedicated seven years at Stanford University Human Performance Lab, to identify these key metrics.

- Cadence: how frequently your foot contacts the ground every minute.

- Bounce: the vertical displacement of your body while you run.

- Ground Contact Time: the amount of time your foot stays on the ground during each step.

- Braking: the decrease in speed your body experiences on each step.

- Stride Length: the distance between the initial ground contact of one foot to when that same foot hits the ground again.

- Pelvic Rotation: how much your pelvis tilts on three axes. It is a measure of how stable your core is.

These metrics are important to running because there lie valuable insight and data that can tell you how to run better, how to reduce your risk of injury, what area needs improvement, and what to do to fix it. While there may be no such thing as one perfect form for everyone (at least none that has been identified), there is bad form, and we have a pretty good idea of what poor running biomechanics looks like.

For example, a low cadence value, a long stride length value and increased braking are often an indicator that you may be over-striding and are overloading your hips and knees, putting yourself at risk of injury. In this case, increasing your cadence while maintaining the same pace could help reduce the risk of injury and help you run more efficiently.

Another example is bounce — otherwise known as vertical displacement. A high bounce value when running is an indicator of inefficient running, as you’re wasting valuable energy on up and down movements, rather than smoothly moving forward to maximize speed and distance. To minimize inefficient energy expenditure, focus on pushing off of your foot with each step so that you propel yourself forward.

While each metric is extremely important in the study of running biomechanics, as research advances and focuses change, new trends begin to appear on what is considered the holy grail of running.

The Latest in the Field

Until recently, the focus for runners, researchers, coaches, and experts alike, was on foot strike – whether you are a forefoot runner, midfoot striker, or the controversial heel-striker. There’ve been many studies and debates on the topic of the best way to contact the ground and how “we’re all doing it wrong” in terms of preventing injuries, running faster, or farther.

Now, the focus has shifted a little further up the kinetic chain to our pelvis (specifically pelvic movement), as well as to over-striding, a far too common cause of injury for many runners.

Pelvic Rotation

The pelvis is the starting point for all movements. It makes sense – both from an injury prevention standpoint and an enhancing performance standpoint – to pay more attention to our pelvic movement as we run. Physical therapist and coach, David McHenry explains:

“The foot is just the end of a big kinetic whip–the leg. Core and hips are where every runner should be starting if they are concerned with optimizing their form, maximizing their speed and minimizing injury potential.”

Pelvic stability is the measure of the movement of our pelvis on three separate planes: sagittal, coronal, and transverse, which correspond to tilt, drop, and rotation, respectively.

Pelvic Tilt. Most effectively seen from the side of the runner; it is the movement of our pelvis on the sagittal plane. Try sticking your butt in and out to feel what an exaggerated pelvic tilt movement feels like.

Pelvic Drop. A common affliction of unevenly developed and weak muscles and levels of flexibility; it is most effectively seen from the front (or rear) of the runner. To get a sense of what this movement looks like, try swinging your hips from side to side.

Pelvic Rotation. Much like its name, this is the movement of your pelvis from left to right (or clockwise and anti-clockwise). Often an issue for over-striders or misalignment, a large pelvic rotation is an indication of driving your stride by throwing one side of your hip forward rather than pushing off of your foot.

Of the three pelvic rotation movements, the two most problematic ones are tilt and drop; tilt has everything to do with your posture and back strain, and pelvic drop has to do with pressure on your knees as you land. These are most likely to be the cause of injury to the back and knees for runners.

Tips for Improvement

Unlike cadence, which is fairly easy to control as a runner, pelvic rotation tends to be more of a challenge because it’s difficult to conceptualize such a subtle movement on a central location of our bodies without external eyes on you (i.e., a coach).

Here are a few coaching cues from the Lumo Run coaching model to help you reduce all three pelvic movements during your run:

- Imagine you are preparing for a punch to the stomach and keep your abs engaged. This will help reduce pelvic tilt.

- Picture a finish line ahead of you and that you are about to cross it. When crossing, lead with your hips. This will help reduce pelvic tilt, as well as rotation.

- While running, try to maintain a 2-inch window between your knees. This will help stop your legs from crossing over, and reduce pelvic drop.

Over-Striding

Another area of focus in recent biomechanics research is over-striding. When trying to run faster, we tend to fall into a nasty habit of controlling speed by increasing our stride length rather than increasing our step count. It is one of the most commonly seen form faux-pas for runners, and it’s also one of the most common causes of injury. So what does it mean?

Overstriding is when your foot comes into contact with the ground in front of your center of mass (or your pelvis). Another way coaches describe it is when your tibia (lower leg bone) comes in contact with the ground at an obtuse angle — rather than perpendicular to the ground, as it should be. The ideal is always to land with your foot directly under your body and not in front.

How Should My Foot Land When Running

Take a look at Meb Keflezighi from the 2010 Boston Marathon. Notice how his stride length is of an incredible distance, but each time his foot hits the ground, his legs are at a nearly 90-degree angle and his pelvis, as with the rest of his body, is directly above his foot.

Video 2. Slow motion gait of a marathon runner.

When you’re running, each step you take is already loaded with tremendous force from your body-weight and the speed at which you are coming in contact with the ground. This is amplified in all of the wrong places when you over stride, as all of that impact is transferred at an angle through your foot that loads the hip and knee and puts your body at high risk of injury.

In 2011, Dr. Bryan Heiderscheit, a now famous expert on overstriding, showed in his study that overstriding is tied to a high bounce value. The longer the stride on each step, the higher you have to jump in the air, which results in excessive vertical movement of your body while you run and a harder impact as you hit the ground. Not only is excessive bounce another common cause of injury, but it’s also an inefficient way to run as you waste your energy moving up and down rather than smoothly forward.

Tips for Improvement

When trying to fix over-striding, the quick and dirty solution is to increase your cadence — otherwise known as steps per minute. But coaches and experts alike caution against sudden and drastic changes to your running form, as this could result in far worse injuries than the form you are trying to correct.

If you know you are an over-strider, try slowly increasing your cadence by five to ten percent of your preferred cadence at a time. A study by Cavanagh and Williams (1982) found that most runners select a cadence and stride length combination that reduces their metabolic cost (a measure of energy and how tired you feel). Suddenly increasing your cadence over the recommended ten percent requires a large metabolic cost and tires you out a lot quicker – which makes it difficult to run in good form.

Here is a Lumo Run coaching cue you can use to increase your cadence while out on your next run:

“Imagine you are running through a puddle and you are trying to make as little splash as possible. This will help you quicken your steps, reduce ground impact and shorten your stride.”

Breaking Ground

We’ve talked a great deal about running biomechanics and the importance of the insight it can give runners into their running form for improving performance and reducing the risk of injury. The challenge, however, has not been to accept its importance, but rather an accessibility to this kind of sophisticated, lab-grade data.

It’s one thing to be mindful of not overstriding, or trying to run smoothly forward without bouncing, but there hasn’t been a way for runners to know their exact pelvic rotation value on a specific run, or what their bounce was like at mile two.

One of the ways Lumo Run is breaking ground in the running community is by making this running biomechanics data accessible to you every time you go out for a run. Through the small sensor embedded in the waistband of the Lumo Run running shorts, it captures key running metrics to coach you to run faster, farther and decrease your risk of injury.

Lumo Run is available for pre-order now at Lumo Bodytech.

Please share so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

This is the reincarnation of the 2010 Myotest RunCheck stride analysis, good to see.