Steve Magness is currently the Head Cross Country coach at the University of Houston for both the men and women. Magness coached professional runners Jackie Areson (4:12-1500,15:12-5k), Sara Hall, and Tommy Schmitz (1:49/3:39). Jackie Areson finished 15th at the 2013 IAAF World Championships in Moscow. Magness has written many excellent articles on endurance training on his website the Science of Running. Since many readers are interested in speed and team sports, the focus of this interview is how conditioning and training can help the more explosive athlete.

Anyone who has not picked up a copy of his groundbreaking book on endurance training is missing out; it’s a bible of running and endurance and is extremely well written. The book can be found on Amazon at The Science of Running: How to find your limit and train to maximize your performance.

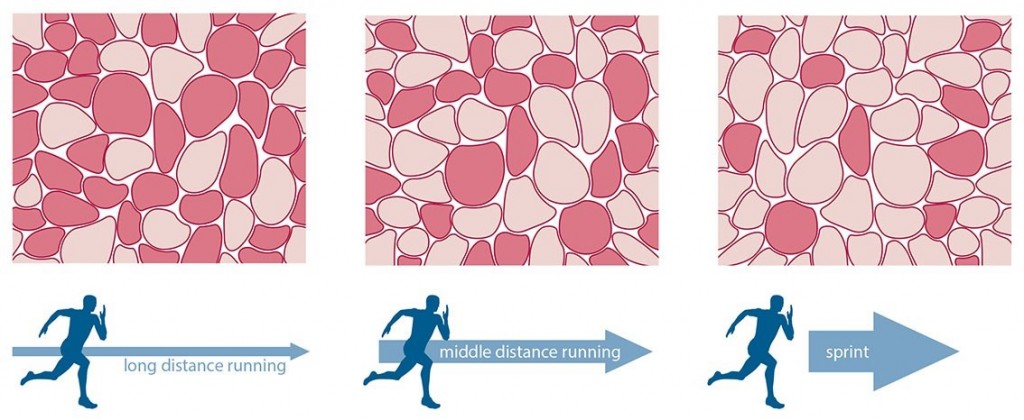

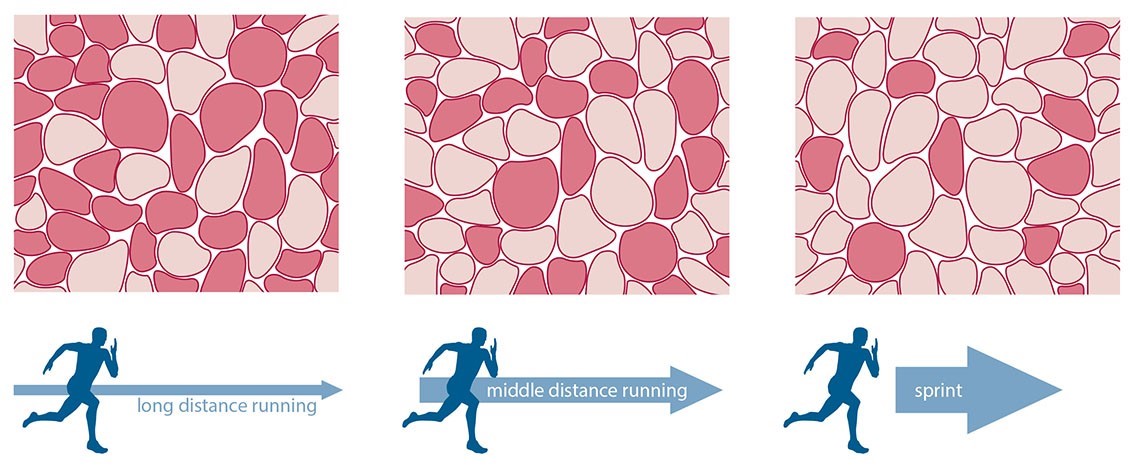

Muscle Fiber Types

Freelap USA — Your book really went into a lot of discussion about muscle fiber typing and that was a very fresh perspective on the individualism of athletes and training. With more talented sprinters having more faster fiber types, what ways should coaches look at monitoring and applying a precise dose of tempo running if they elect to use grass runs? Many coaches will not do any running for conditioning and some are religious about using tempo runs. Any thoughts on keeping athletes fit without conversion fears?

Magness — If you look at the disparity in sprint training when looking at the various successful programs, it always astounds me the different ways in which sprinters get their “aerobic” or tempo conditioning.

While fear of fiber conversion is a real phenomenon, I think you have to look at it on an individual level. I would look at classifying based on fiber type, and by that I don’t mean you need to go get a biopsy, but instead look at surrogate markers of power, strength, explosion, and reactivity to discern where the sprinter falls on how FT fiber dominant he is. From there, to me it seems logical that the more FT dominated, the less purely aerobic/ST work you would do. So for extreme FT dominated athletes your looking at doing your tempo work using shorter extensive intervals that are still fast, so maybe 8×200 starting at 30 and working down, while with an athlete not as FT orientated, you can get away with slower longer work much more. And in fact they may benefit from that training much more because if they have a higher percentage of FT-a or ST fibers, then they need a lower intensity stimulus to increase the mitochondrial adaptations in those fibers.

You can check throughout your foundation phase to make sure power levels are not dropping too much by the use of any number of reactive or power tests.

The bottom line is you train towards the individual’s physiology. That’s why you have programs that are successful that still have 2-3mi runs in it and some that don’t do anything over 400m.

Comparison of muscle fiber type for distance runners and sprinters.

Carl’s Take: Fiber testing can be done with estimations from non-invasive methods such as MRI testing such as the Muscle Talent Scan from Belgium (Above). I have found the use of LPT systems such as Gymaware combined with blood testing to be very clear when profiling athletes as well. The Bosco tests are having a rise in popularity again because jumping is a great way to train and monitor athletes. I prefer weighted jumps to create a training effect but unloaded testing is helpful. Fatigue rates with higher fiber types are always going to be more dramatic even if they are in great condition, and sprinters should be very careful with drops in velocities or higher volume running programs.

Muscle Tension and Tone

Freelap USA — In your book you discuss the sharpness and muscle tension or tone for endurance athletes. One can make a case that sprinters tone of muscle can be more vital for performance and your chart seems to be in agreement with muscle diagnostics (Myoton readings) and sports massage techniques. Besides trial and error, what suggestions do you have for ensuring that tone is optimized from training? Several coaches are manipulating other variables besides surfaces. Any ideas here?

Magness — This is where art is a little ahead of the science. We can measure tension to a degree with devices like the Myoton, which would be nice to have. But the reality is most of us don’t have that option. What I’ve found that works the best is simply relying on your athlete’s feedback and tracking that. I use a simple 1-5 scale of daily muscle tension that an athlete fills out on their smart phone before and after a workout. What we then do is correlate this to the training done and the modalities the athlete has used (massage, hydrotherapy, etc.). If you track the data long enough you start to see patterns emerge and can almost come up with an individual plan for raising and lowering tension.

I’ve been surprised by the disparate reactions some athletes have to the same modality. For instance, in distance runners the running surface makes a huge difference to certain athletes, and running on a soft surface like grass the day before a race can absolutely destroy tension levels.

Carl’s Take: Muscle tone is one the most important injury parameters available and it’s shocking how professional sports create dashboards on very indirect variables to risk. Coaches have a wide variety of options to estimate muscle tone, and Myoton is a growing tool for doing rapid evaluation of passive muscle tone. In the future coaches and therapists will work to not only manipulate fatigue and power, but also manage tissue texture with the right combination of training and recovery techniques. Manipulating surfaces, adjusting training volumes, tinkering with warm-up routines, and even timing of massage all interact with muscle tone. I have a dashboard that uses this with some athletes, but the key is making sure the decisions in training are logical.

Blood Testing

Freelap USA — Blood testing is a cornerstone for endurance athletes but much of the emphasis seems to be only Vitamin D and Ferritin levels. With adjustments needing to be made for hematocrit and hemoglobin from blood plasma changes diluting the scores, what biomarkers are you looking at to ensure athletes are not running themselves into a performance grave? Joe Vigil made testing mandatory so what are your ideas on the subject?

Magness — In addition to the obvious ones above, I like to measure TSH, cortisol, DHEA, and T:C ratios. Blood work gives you an overall view of how the system looks. There is no perfect marker that tells us about overtraining or over reaching and I don’t think there ever will be because there is not one simple cause. The above markers give me a snapshot of the hormonal system and how it’s functioning. TSH gives you a snapshot of thyroid function, while cortisol gives a decent marker of stress, which is even better when combined with T:C or for women DHEA: C ratios. If these markers are off significantly then the likelihood of positive adaptation to training is diminished. As an example, I’ve got some good data throughout the years that looked at athletes adapting to altitude with changes in RBC mass. We’d have certain athletes who didn’t respond well even though their ferritin levels were high. When trying to find a connection to see why they didn’t adapt, I noticed that almost every one had high cortisol levels at the time of the altitude camp. They were already at an elevated stress level so they couldn’t adapt to the new stressor of altitude.

In the future, we’ll go beyond blood tests to look at stressors. I think there’s some great new technology out there that could help give us a clearer picture. In particular, the use of new portable EEG looks hopeful for analyzing psychological and emotional stress.

Carl’s Take: Blood testing is getting faster, cheaper, smaller in sample amount, more comprehensive, and less invasive now. While many are waiting for the future, those who have invested in testing athletes can see what biomarkers are warning signs and what are cardinal signs of overreaching and overtraining. Estimations of stress with HRV are great ways to connect the testing periods with a string of general stress, but eventually autonomic stress is a trigger to more specific and applied testing. If you are not getting complete blood evaluation or have problems analyzing the scores, think about using a third party company or work with a sport scientist who is very experienced.

Acidosis, Lactate, and Byproducts

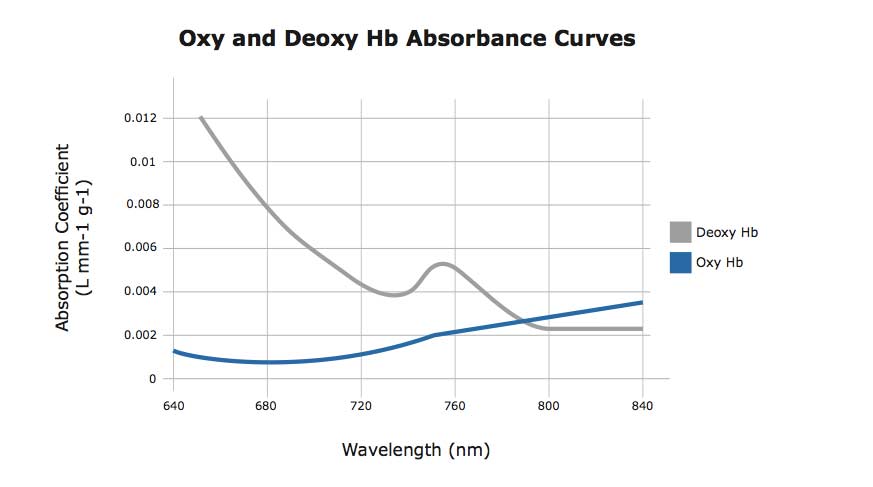

Freelap USA — Acidosis, lactate, and byproducts are a complicated matter when working with the 400-800m crowd. What are some good tests that can leverage invasive testing such as lactate testers and non-invasive testing such at the MOXY monitor? While measuring different elements what could be done to see similarities and differences if one elected to use both? Any creative ideas on using such devices for team sports such as soccer or speed athletes?

Magness — For lactate, the key is knowing what you are trying to look for. It’s my belief that regardless of whether it’s for team sports or an 800m runner, we need a test that gives a reflection of the total capacity of the system, and then a test that gives an idea of we deal with the lactate. For this reason, I recommend using a max test of 400m to get an idea on how much capacity our anaerobic system has. Then combine it with a progressive interval test to see how we deal with it. For distance runners that could be something like 4xmile plus a max 400m. While for an 800m athlete you might do 4-5x600m +400m. For team sports and sprint athletes, what I would recommend is combining the max test, with using lactate after extensive but progressive interval training to see changes in lactate as speed increases.

I’ve been fortunate enough to test out the Moxy and it’s a great little device. You can actually correlate it with the lactate tests and get a good idea of what’s going on in the muscle. You have much greater flexibility here with the device. I actually think the Moxy will be of great use in designing recovery periods between sets and reps. You can map oxygen saturation drops after different kinds of workouts and see clear differences, but also during the recovery portion. Tracking rate of recovery of the muscle oxygen saturation over weeks and months should give you an idea of if you are adapting in the right direction.

Oxy and Deoxy Hb Absorbance Curves

Carl’s Take: The MOXY monitor is a non-invasive device that is getting direct data from the muscle tested, and lactate testers get a measure of the total body lactate changes. Both have similarities and both have unique benefits. I have been testing with lactate testers for only ten years but find them very valuable for speed endurance runs in the spring and high volume sets of acceleration in the fall. My only experience with Sm02 is doing reporting documents from European coaches and didn’t really get interested in buying one until Randy Huntington and Steve Magness shared their opinions on the device and it being under a thousand dollars. Keep in mind if you are not timing first, all the data from physiological estimations is not helpful.

Monitoring

Freelap USA — Monitoring is popular now with coaches and athletes and you have talked about different methods that are very simple in your blog and in the book. Any thoughts on the power of a simple short word analysis for athletes reflecting in a journal? Coaches don’t have much time to interact with athletes all the time and having some thoughts, brief if needed, shared could make better use of the precious time. Any suggestions?

Magness — Absolutely. The best monitoring has to be simple and useable. Most of the data collected by coaches is never used, even if it would give some great meaning. In the case you mentioned, using short descriptive words to explain how the workout went, felt, etc. is a fantastic way to get inside how the athlete is actually doing. I’ve toyed around with having athletes fill out a simple training journal on their phone where they include 3-5 words describing the day, which then is relayed to the coach. It gives great feedback to the coach without having to pour through data or long conversations. And once again, we start to see patterns if you track it long enough.

To end with though, one of the simplest and most useful things I’ve done in monitoring is simply have athletes rate the day either red (bad), yellow (avg), or green (good), based on how they felt. I do the same color-coded rating for the same day. It then pops up in my training calendar and color codes that day, and I can see patterns distinctly thanks to the color-coding, but also see where the athletes and my analysis were completely different.

Thermographic Panel

Carl’s Take: Dashboards are all the rage right now as data is now the new currency for several coaches. At the end of the day communication starts with honesty and reinforcement when working with athletes. Better data is not just objective, but about the relationship and environment athletes are dealing with. The brain is a final frontier with many coaches and performance specialists, but the spirit or emotional side is just as important. The above dashboard is from Haloview, showing muscle status based on objective data.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

Great interview and I’m looking forward to picking up my copy of “The Science of Running.” Topics such as those covered in this interview may be signifying an evolution in the distance community’s mindset as it relates to pounding the pavement.