Brisbane Broncos Coach Dan Baker celebrates with league trophy.

Dan Baker is one of the world’s leading authorities of strength and power training for sports athletes. He has a PhD in sports science specializing in the testing and training of strength and power and has the scientific knowledge and practical know how to implement effective strength and power training for sports athletes.

Coach Baker’s resume and accomplishments include:

- Brisbane Broncos Rugby league team strength and power training coach since 1995 with title winners in 1997, 1998, 2000, and 2006.

- Former champion powerlifter and powerlifting coach.

- Strength and Conditioning Coach to elite national and international level athletes in rugby, powerlifting, diving, soccer, track & field, netball, mixed martial arts.

- Level 3 Strength and Conditioning Coach and Master Coach of Strength and Conditioning as recognized by the Australian Strength and Conditioning Association.

- National President of the Australian Strength & Conditioning Association (ASCA), a not-for-profit organization recognized by the Australian Federal Government with the goal to educate and accredit strength & conditioning coaches in Australia.

- Lecturer to all levels of ASCA coaches, from Level 1 beginner Coaches through Level 3 Elite Athlete Coaches.

- Educator of Strength & Conditioning Coaches making the science easy and telling it straight.

Freelap USA — When designing a program that needs aerobic and power, is it better to focus on speed and player size first rather than keeping rugby athletes fit? It seems that the first thing to go when a player ages is speed and many team coaches tend to focus on conditioning. Considering the year round requirements and the need to develop both power and conditioning, how do you manage the long term development of players? Is a period of time needed to step away from doing too much conditioning or conditioning at all?

Coach Baker — A player needs both qualities and they are equally important to be successful in the NRL competition where I worked. The key is developing latter teenage years till early 20’s. We try to attain these things with a cumulative and progressive overload across a few years. This is when they have not made it to the elite pro level, but have generally been talent-identified as having the potential to play NRL. So at this time, they are playing in an appropriate competition (either Under 17, 19, 20 years comps or the second division) and this is the time to develop these qualities to the utmost because:

- These are their best years for recovery from training stress due to hormonal levels, etc.

- They have no real life stress.

- Whether they win or lose these competitions does not mean much to the pro club, as compared to the elite pro NRL comp.

All our years and years of data suggest that is pretty simple to develop both aerobic and strength at the same time, you just have to intelligently plan training and have some basic general aerobic fitness first (to help with recovery). By planning I mean for example within-week planning, days with a high aerobic running conditioning element in the Prep Period, we would do upper body strength/power work and on days with lower body strength work, we would do more speed/agility first, or tackling contact or wrestling work (heavy upper body emphasis), second. We try to manage the global load and understand the interference or impact of each type of training upon the other and help with recovery.

And more longitudinal planning across the Prep Period and across 2-4 years is vital. Basically, once the player is > 22 years and in the NRL, we often cannot overload the players to such an extent to induce any large improvement in strength or aerobic conditioning. It is just maintenance and management at the highest NRL level. So the big changes in strength and aerobic conditioning must occur between 17-21 years of age.

My former coach of the Brisbane Broncos would always want the player to shed 1-3 kg as they got older to help maintain speed and negate the necessity of extra conditioning. We always found our players had to do less conditioning as they got older anyway – playing elite NRL for 6+ years, you have to be fit. For example, when I have analyzed the data, the running Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS) of players who have played for > 3 years at elite NRL level is 4.42 to 4.6+ m/s while those 1-3 years is, on average 4.36 m/s and those who never make it is, on average, 4.2 m/s or less. So older players, if they keep their body weight down and are smart, do less aerobic training because that quality is already well developed, so the emphasis on its maintenance is intensity not volume and thus we can do more quality speed sessions with them as hey older, not less!

If a young player really needs to gain weight, we have to use the 7-week period when there is no training scheduled (i.e., their off-season). I would write a 3 day/week program to do and give them the dietary tips, explaining “window of opportunity” – so while I say we can gain strength, size and conditioning at the same time, of course it is even easier if there is no conditioning or skill training.

“So basically planning is paramount ~ planning within day, the week, the period and multi-year planning.”

Freelap USA — Your educational wall posters suggested a regeneration session as part of the responsibility of players. Various modalities and protocols you have used include recovery drinks, compression treatments, sports massage, and conventional rest and sleep. Besides player subjective feedback, what type of tracking do you see are ways to see the impact of such treatments? Rugby is always a little ahead of the NFL and I am sure this can help teams in the US get an idea of how data from player accountability can show who is on board and who needs to think of going elsewhere.

Coach Baker — Those wall posters were Dean Bentons brainchild, to emphasize the mutual obligation we, the staff and players, must have. Recovery protocols were compulsory during my 19 years at the Broncos and just kept getting better and better as science and practice from around the world informed us of different methods. You have to understand that Australian pro sports are all strictly ASADA/WADA tested, so players are subject to ASADA/WADA testing 24/7/365 and they are random-tested a lot. The top 10% in the NRL also have the WADA biological passport. So you cannot get to the top and recover through pharmacological means. Drug use is a 4-year ban!

In Australia, recovery modalities are important. Every session of training has a recovery modality to be performed afterwards plus a recovery drink(s). Besides subjective measures, we would use GPS data, look at total meters, aerobic meters (3-5 m/s), anaerobic meters (5-7 m/s) and sprint meters (>7m/s), number of big collisions (G forces) and so on. Look at power output and strength scores weekly in the gym, compared to PB’s and the previous year’s scores for the same time period, etc. We also measure hydration, skinfolds, flexibility, etc. every week.

We do not really worry about what we do when we have the players with us, BUT WHAT THEY DO AWAY FROM US IS ALWAYS A CONCERN! This is where players must take accountability and understand the mutual obligation we have toward each other and the club.

If their skill sessions decline in quality, their strength/fitness qualities decline or their actual game performance decline, we ask why? We analyze GPS high quality meters in simulated game/skill sessions – is that player getting the same data as his opponent in the session? If not, why? Whose fault is it? We would measure hydration status 2-3/week – we found that poor hydration level is a precursor to lower body muscle strains (calf, quad, and hamstring). Is the player hydrated? That is the easiest thing to ask someone to do, to come to training hydrated! If not, why? Whose fault is it? Flexibility, tested weekly. If it declines 5% across the board, we found increase likelihood of injury. If it changes, why? What do we do? Sleep, we spent some money on research, a top US company that aids the military – irrespective of the sport, I think younger pros have poor sleep habits, they play computer games or have their phone on, waiting for booty calls – this disrupts sleep and hence recovery. Are they having good sleep? If not, why? Whose fault is it? Body weight and body fat levels, we know they correlate negatively with aerobic and speed scores, once we have got to optimum levels. They are measured once every week. Is there a negative change? If yes, why? Whose fault is it?

We basically educate the players about these things, that all the recovery strategies are cumulative and sometimes, so are “breakdown injuries”, an accumulation of stress to an area. Did the player help in mitigating that stress through proper recovery or was it our fault in the coaching staff. We, the staff do what we can and leave no stone unturned to help the players, but what are they doing away from our prying eyes?

All the little recovery modalities in the world won’t make up for a bad diet punctuated with regular junk food, poor hydration, poor sleep habits and excessive alcohol intake on the non-designated days. Those things are the responsibility of the player/athlete. I have a saying, “Professionalism is not about a pay-packet, it is about a state of mind”. Coach Turley from Stanford University has a similar one, “Align your choices with your objectives”.

Freelap USA — The Shed of Dread is what you use for players that can’t do a full practice and many of the options are to work around injuries. A lot of soft tissue injuries occur with the hamstring and groin areas, specifically non-contact. What do you see in the weight room with athletes with poor training backgrounds being a part of this problem? Australia doesn’t seem to be that polluted from the balance boards and silly functional exercises, but no country is fully sterile. Is a comprehensive lifting program still the best injury reduction variable for muscle injuries or are team coaches still needing to be educated on practice and weekly set-ups? Is a combination a part of the equation and what is your insight?

Coach Baker — Our S & C coaches at pro sport and Olympic athlete level are well trained and educated, so they leave the gimmicks and fads to the personal trainers whose pay-packets depend upon stimulating bored, lazy clients. Most of the balance board and Bosu ball stuff is done by personal trainers in Australia – they are not allowed to work with high level athletes in Australia.

With regards to training in the gym, I always emphasize a comprehensive lifting regime – full squats, partial squats, split squats, 1-leg squats, pistols, step-ups, lunges, lateral lunges, walking lunges, RDL’s, 1-leg RDL’s, hamstring and glute bridges, and the list goes on and on. There are generalized full range strength movements, shorter range movements, unilateral movements, higher velocity movements, and again, so on and on. Of course we need mobility work as well as technical drilling to transfer gym strength to running.

I never saw too many athletes with poor training backgrounds at NRL level, mainly just developing players who we may have recruited, we would have to fix them up.

The AFL have the longest running continuing study on hamstring injuries in the world, so they are a wealth of knowledge on hamstring and groin injuries (AFL is different to NRL, but both are collision football sports played in Australia). They have found the biggest predictors of hamstring injuries are:

- Previous hamstring injury,

- Lower back issues,

- Smoking (well, no one smokes much now, but they have data from over 40 years), and

- Race (yes race, don’t get all offended now).

Groin issues are related to above but mainly also due to large or sudden increases in training volume – these groin problems typically occur in the latter teenage years when we are trying to prepare the players for pro level (as in answer 1 above) or in the latter years of a players career (>28 years), when older players try to maintain the same volume of training or they take time off and then when Pre-season training commences, the sudden increase in training volume breaks them.

So in knowing these facts, you modify training for the at risk players. We know from studies in AFL players done at ECU that running gait is negatively modified in hamstring-injured players after about 20-mins of continuous, but intermittent speed running. We know that large running volumes affect hip flexor tightness, affecting the function of hamstring and adductors. We know that younger, 17-19 year olds and >28 years are at risk for groin injury or pubic inflammation. We know that previous hamstring/groin injury increases this risk. We know weak hip muscles or imbalances increase the risk. So these factors help us to more effectively plan training, especially for “at risk” players.

I also want to point out it is easy not to injure someone at training – put them on a balance board, doing Mickey Mouse exercises ~ you won’t get injured at training, but you also won’t improve as an athlete and within weeks, you will be smashed to pieces by the opposition and get injured then!

So while we know all these things, injuries can still occur – coaches don’t follow the plan of the session (keep the players going longer or harder than was planned), the player had poor hydration, there was a bad collision and so on. I will give an example. Once we did a speed session, but a skills coach wanted to do some extra work afterwards with our main speed players. The next day the fastest player strained his hamstring 5-minutes before the end of the main team conditioning/skill session, which has a large volume (but he also had great aerobic fitness so we knew that wasn’t the issue). When we looked at the GPS for the previous day for the player (whose Max Velocity was 10 m/s, which is very good for NRL players), we found that his high intensity meters with the S & C staff was <350 m at high speed but he did an extra >500 m at high speed with the skills coach! Sometimes people/coaches are selfish; they want more, more for them, but it impacts on the global load possible for the athlete and the work of the other coaches. Two take-away points from this experience: we started keeping a better eye on the skills coaches and we needed to better lay down the facts to skills coaches. In this case, the skills coach just didn’t realize the extent of high speed running that this player was doing in this “extra session”, so it is education, showing him the data, making sure he understood the impact.

I think comprehensive training is important but that comprehensive planning of training is vital and this may entail some individualization. The planning of global loads, but especially the total running loads and high intensity and high-speed running loads is vital to reduce the likelihood on injury to the hamstring and groin, especially in “at-risk” athletes, as is the strength program.

Freelap USA — Testing athletes seems to scare a lot of teams in North America because tests are often maximal, such as jumping and sprinting. Coaches are worried that players may be a little lazy and not go all out or go all out and get hurt. What are your thoughts of testing power and speed with athletes? What do you think is needed in modern sport to keep driving performance objectively?

Coach Baker — I believe in testing, how else do we evaluate our training programs or the motivation of the player? What I always did for strength, power or speed tests was only test players when they were peaking and fresh for testing, that way there is minimal risk. Also why test unless you expect to at least equal or beat your previous best (or at least be close, if your recent training would suggest that you will not PB).

I never tested strength/power etc. when the players returned to training. Why would I, they are not in shape to PB or anywhere near it and what would I be evaluating, the effect of doing bugger all training during their designated 7-weeks off? So I would only test strength and power if we had >6 weeks in the General Prep (sometimes we would only have 3-4 weeks, so no testing then) but everyone would be tested at the end of Specific Preparation when the training load was reduced etc., and players had performed anywhere from 6 to 14 weeks of Preparation Period training.

So think of a weightlifter or powerlifter competing, the last heavy session done 7-12 days before hand pretty much tells you what your max will be in comp. That is what I did for strength testing, the previous weeks lifts determined our strength and power goals for the test week. Also I chose every single weight the players used. Every weight for every set, for every exercise, for every training session and test, for every single player, always! So they could not choose some ridiculous weight for a 1RM test. I chose their attempts, their warm-ups etc., and therefore was responsible for every choice and every outcome. And all my choices were based upon previously performed data.

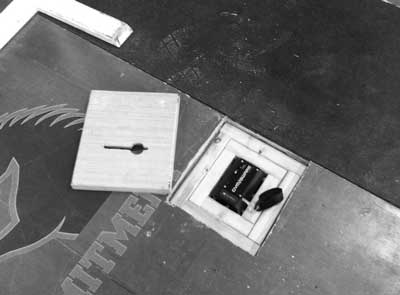

Coach Baker is known for making sure the applied needs of data collection are always considered in order to make training conditions ideal.

In-season we test all the time, it is called training! For upper body we would do a max effort set of 3 or 5 reps on the bench every 2-3 weeks (using different constraints such as bands, chains, normal) comparing to established PB’s. For squats, we work up to a 5 RM or 6 RM but for only 2 or 3 reps, every 6 weeks, emphasizing velocity. For power, you can assess lifting velocity or power every session or for cleans/jerks, work up to a heavy single, double or triple every 6-weeks! When we tested strength and power, the players loved it, it was competitive. The winners in each category go on a board, but so did the losers, labeled “Prison B**ch”. So even among the not-so-good, there was intense competition to not be at the bottom. We did power testing weekly to determine the bottom rung athlete, both Prep Period and In-season.

Of course aerobic testing of MAS would occur soon after returning to training, but that is less risk compared to strength, speed or explosive tests. Even so I would rather test MAS 1-2 weeks after return to training to even reduce the risk for that.

We would not even bother doing speed testing during the first 4-weeks or so of Prep Period – the running volumes for aerobic conditioning were too high, we would not see any speed improvement and the high-volume generated fatigue would increase the risk of hamstring or calf injury, so why bother? So real speed training (not technical drilling) could only effectively occur during the last 4-6 weeks of Prep Period, after the aerobic base for the season had been established and accordingly the volumes of running could be reduced and the speed work increased. So don’t bother to test speed till then.

In-season for speed, we never tested but over the last few years, GPS data from training, testing and games could tell you if the player was attaining max velocities. We even have cases where players attained higher max velocities during games than they did in speed tests!

“So testing is vital, but do it at the right time.”

Freelap USA — Your thoughts on GPS and HRV are very honest and upfront with the expectations of players. With many sports focus on fatigue, you seem to be focusing on managing power, a better mindset as it is positive. You see all the data and understand the game, so what suggestion will you have with teams in the US being worried about athletes getting enough rest? Your athletes in Australia are doing a lot of output, both in running and the weight room and New Zealand and South Africa are no slouches either. How much is sport psychology a part of managing player load?

Coach Baker — GPS and HRV just give us data – we need to interpret data and then determine training. Firstly, on GPS. GPS measurement is very Australian – Catapult is an Australian company, we have been using it in NRL, AFL, rugby union, hockey, and soccer for years. We even use it surfing. It tells you lots of things but it does not tell you how to train. At the Broncos in the last few years that I was there, we would expect players to attain 30% of a skill session at a certain m/s. If a player did not attain it, and his opponent did, again, why? So GPS allows us tracking, helps inform our choices for managing training etc., but it also puts accountability on the player and his performance. You the player are expected to attain certain m/s, why did you not attain them? What are you doing away from training that prevents you attaining these goals, because we are managing everything else done here at training? Is your lifestyle negatively impacting your performance? Be accountable for your performance.

I was of the thought that using HRV would be difficult in a team setting, for compliance reasons and also I don’t like “something” telling me how to train athletes. But more recent advances in certain types/brands have shown me how they could be used in a team setting, compliance wise, at least. Specifically I like the iThlete method and finger sensor, which could be used, as it is not excessively time consuming. I use iThlete every morning, takes 2 minutes, so we could use that easily in a team setting and expect compliance.

Also, what I found is it distinctively shows me if I had a few beers on a Friday night, you just can’t hide that fact. For example, if I had a few too many beers, my HRV is low 60’s at 5:30 am when I typically wake-up, but during the week it is low 80’s or after very hard training days, high 70’s. So given the advancements of the sensors and the ease of use, I would now use the HRV as it won’t lie about what is happening away from training. But HRV wouldn’t tell me what to do – I would use it to see what the player is doing “unprofessionally”, stuff that hinders their recovery and thus hindering our training efforts. Because as S&C staff, for example, there should be no reason why one or two athletes in a team setting one day suddenly score low 60’s when everyone else is 70+ because we would have planned and managed the global training load so that HRV’s would be similar ~ in this case we would know it was a temporary lifestyle factor impacting recovery. So technology would be giving me objective data compared to subjectively, (where there may be lies told) and then I/we (S & C etc.) would make decisions about training content and discipline.

Coach Baker ensures recovery is programmed and supported, but athletes are pushed, not babied.

Also what we have seen from fatigue science is that a huge proportion of fatigue is mentally driven or perceived, but there are physiological markers of fatigue as well. Stu Cormack worked as a S & C coach for one of the top AFL teams for years and did his PhD on monitoring fatigue and performance etc. He measured testosterone: cortisol ratio, creatine kinase, leg power etc. weekly as well as subjective data (how do you feel about training today?). They all correlated, but guess what takes less time and money – asking them about training, how they feel ~ provided they don’t lie!

So we know that how the player feels is important but that also, there are tests that are objective indicators ~ we need both.

So what we need to do is find out why a player feels fatigue and/or why their tests may be lower. What/who is to blame? Is it us, the S & C staff for not managing the global load or individualizing the load for an at risk player? Is it the technical/sports coaches, not sticking to the planned load? Or is it the players’ lifestyle? We have seen that often nowadays it is the player’s lifestyle, a sense of entitlement attitude exists for some younger players. They want to be “fresh” and not sore, to not push the boundaries of their physiology, to have all the best supplements, massage and physical therapy, day in, day out. Really, can we alter 200,000 years of human physiology without stress?

I mean, in the end, if you are playing NRL, AFL, rugby, MMA, you are going to be really fatigued during the contest and you need to be perform when you are fatigued. You can’t call time-out in these sports ~ you need to push through. As Winston Churchill said, “If you are going through Hell, keep going!” So you need to understand fatigue, training load and the impact of these upon your own performance. The NRL season is 30+ weeks, you can’t be tapered and fresh for this long, you need to perform and win regular season with some fatigue from training. You then taper and reduce load for the finals, that is when you want to peak and feel good!

I don’t want to portray that I want players to be Spartan or live an un-enjoyable life, far from it. But you can only have one guilty little pleasure. So if you like a beer at the end of the week, then don’t eat junk food and go to bed early; if you prefer junk food, don’t drink etc., if you’re a booty person who stays out late on the hunt, then make sure everything else in life is immaculate or you won’t survive in top level sports. And choose the appropriate times/days for these guilty pleasures. You can’t be doing booze, booty, and burgers throughout the training week and expect to perform at high level sports for an extended period. A positive attitude comes from knowing that your training preparation, your skill/tactical preparation and your life-style preparation are all dialed in and in balance. In a harmonious balance. Knowing that yes, you are allowed your one guilty pleasure, at the right times, because you have earned it through hard training and discipline at other times. When an athlete is feeling fatigued and others are not, we need to check off the lifestyle factors first – booze, booty, burgers and attitude before we start looking at training content! In the US, the saying is “Man Up”. In Australia, the saying is, “Harden the f*** up” or stop being a sook, stop complaining, stop giving pathetic excuses and do what needs to be done as a professional!

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]