By Carl Valle

Editor’s Note: This is part of a series of articles showing how deeper metrics of bar tracking technology can improve the quality of training in the weight room.

We have witnessed more investment into bar tracking technology during the past two years than the previous two decades. While this may seem like progress, many coaches have not progressed with the technology. Investing into bar tracking comes with a cost beyond the financial side. It requires coaches education and appreciating what the technologies are trying to do. Coaches who jump on the bandwagon to be relevant will be frustrated because they have not prepared their athletes to be aware of the importance of simply following directions and the difficulty of getting measurements on things as complex as weight training, jumping, and throwing.

As a coach, you should consider the following three questions before proceeding with adopting any VBT technology.

- Do you have a training environment in which athletes follow directions in your training environment, respect the training process, and pay attention to it? Any technology requires that everyone take at least some measure of responsibility for it to work well.

- If the information or data isn’t what you want to hear, will you make adjustments or continue doing what you like doing?

- Do you have a clear plan or a realistic goal for implementing barbell tracking technology, or do you feel pressured to adopt it to keep up with the data or technology arms race?

These questions are honest ones, so by all means step right ahead if you are confident that barbell tracking will add value to what you are doing. If you are new to VBT or want to take things to the next level, we will dive into the realities of what is required to work maturely with the technology and methodology.

Measuring mean velocity or peak velocity alone has great value, but if you want to truly gauge barbell performance, you must look at all the numbers to draw better conclusions. Treat each data point like a dot of paint in an Impressionist painting—the more dots, the better the image. In this article, I will review what we have learned from Rate of Force Development (RFD), introduce Mean Propulsive Velocity (MPV), and highlight other common measures of bar tracking to fine-tune workouts for a better transfer. The heart and soul of this article are not just zooming into bar performance, but also stepping back and focusing on the big picture: how barbell performance helps with on-field performance. In sports performance, transfer is king.

Strength coaches have valued bar speed measurements for decades. Now it’s appropriate to see how biofeedback and analysis work together to get better results. The next evolution is understanding how weight training transfers with more concrete numbers, not just past dogma and current fads. Bar speed is an excellent dipstick to test what is going on in the athlete’s muscular engine, and now it’s time to maximize the human machine.

Connecting Bar Speed with Body and Bar Speed—Paydirt

Over a year ago I strongly advocated that the purpose of barbell speed with Velocity Based Training (VBT) was improving ball and body speed. Strength coaches use barbell indices to improve how fast an athlete can displace (locomotion) or how powerfully they can propel balls, competitors, and other implements. Even the Olympics and powerlifting care about the weight outcome, not bar speed, and VBT is a way to help get higher success rates. Coaches and athletes are pursuing propulsion to perform better. Sport success is based on having leg and (at times) upper extremity power to propel a body mass or another mass (large or small) faster or with a higher force. Weight training is a major player in developing this propulsive quality, and the refinement of weight training programming (enter VBT) continues to offer us small yet valuable gains.

A word of caution here. Overreliance on weight lifting as a solution can create problems. While weight training is a great way to gain confidence and create discipline, it’s mainly used to solve three needs and not much else: reduce injuries, get larger, and produce more specific force. Currently, coaches create a lot of misdirection on small nuances like “stimulating” or “potentiation.”

These are fine additions, but without raw strength and power, the athlete misses the primary reasons to lift. The goal when a coach commits to using VBT is to create small and targeted gains that show up outside the weight room. Countless coaches have successfully improved squat and clean numbers in the weight room, but fewer have proven the transference toward improved on-field performance or injury reduction. General weight numbers or data create a case for possible transfer; better numbers seal the deal.

The influx of “evidence-based programs” and various technology measurement options have created a bit of a conflict to training balance. Coaches must be careful not simply to chase numbers. The solution is to understand how and when to use those numbers and make sure they are related to the performance goal. Abstract and sometimes inappropriately positioned sport science may not help a team, and a coach without access to good research is equally ineffective. Instead of seeing science and art as oppositional, why not make the discussion a healthy perspective of how they work collectively?

The good news is the strength game is getting easier to measure and support. With more affordable measurement tools now on the market, you do not need to be a high-profile program to afford the technology to make more informed decisions. In fact, we see that affordable products do the same job (in some cases maybe even better) as more expensive and cost-prohibitive options. Since the conversation is shifting beyond concentric peak and average, coaches fresh to the analytics side may offer an improved approach to outcomes versus those who are static on legacy “norms” from the technology they have used for ten or more years.

Practical Sport Science Is Now Part of the War Room, Not the Ivory Tower

Coaches of any good strength program run solid training sessions while their athletes reflect the results of that training. As more programs transition into information-based training, there will be a phase of frustration resulting from the extra time and technical difficulties in making this adjustment. You need to understand the change (performance improvements) you are seeking when you purchase measurement tools will to some extent disrupt your daily workflow. You cannot expect the tools to fit perfectly into how you like to do things. There is a balance of what you are getting and the adjustments you need to consider to use it effectively.

Since sport science is now part of the war room, coaches are in the trenches making more informed training decisions. Being in the trenches is indeed a cliché, and the image is vivid for pointing out the very real need for something to withstand the challenge of working with a lot of bodies under pressure and time limitations. Coaches need to use every minute properly, and fumbling around with electronics is not something they can afford to do. However, planning is the best way to use time effectively in the long run, as the right direction or strategy maximizes the tactical time. The war room and trenches are complementary, not oppositional if correctly done. Two simple mantras make sense when coaches want to make VBT fit both during training and planning workouts.

- Instant feedback adjusts a good workout plan if needed, but the magnitude is less as coaches increase their experience. Constant adjusting and reaction to planned workouts are a sign of poor program design and analysis.

- Repeated testing of key tests and training exercises shows a cause and effect to the plan over time. As the training data increases, a training program can predict and model better workouts in advance with fewer adjustments.

A simple summary is that as the plan improves, the need for adjustments decrease. But anyone who studies the economy and chaos theory understands that perfect prediction is an illusion. All one can hope truly to get from VBT is higher precision in training and moving the needle by making fewer mistakes.

What Most Articles Miss with Barbell Performance

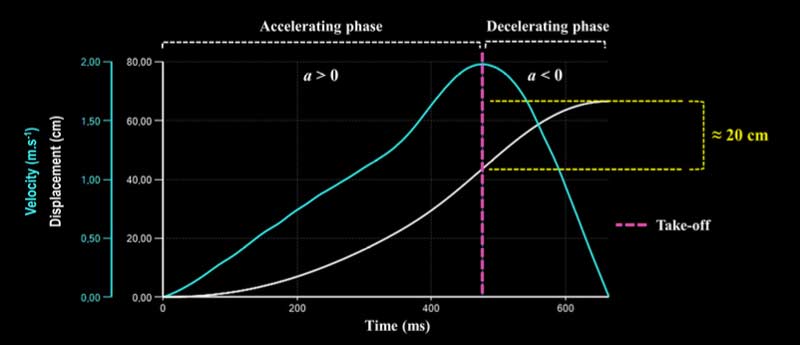

Figure 1. Lighter loads have decelerating phases, but most maximal strength and power programs do not have to worry about them.

My friend Bryan Mann has helped our profession understand the value of VBT. But for every smart guy like Bryan, we have some less-than-brilliant minds sharing their opinions. In several roundtable-like interviews, some of the thought leaders share some great advice here and here, but my concern is that it takes a few more reviews before coaches fully grasp the concept. Summing up this article, this is a fair conclusion: Coaches are looking to evaluate barbell performance as a way to acutely gauge athletes and indirectly help improvement to the sport the athlete participates in.

Most articles that beat around the bush simply describe what is happening at one point in time with a barbell, something that goes directly with the Impressionist painting analogy. To put it bluntly, most approaches to barbell tracking skim the surface and don’t hammer out what can be fully extracted. Perhaps a better way to explain comprehensive VBT is the idea that the numbers on the barbell plates are not the only numbers happening while lifting

Why We Need to Think Propulsion Instead of Just Bar Velocity

Mean and peak velocity are either slivers of time or artificial summaries of the time the bar is moving. The mean is a rough summary of the barbell stoke. Peak provides a narrow snapshot. While valuable, it is flawed without context. Looking at either one is great for adjusting loads and demanding efforts live, but after the workout is done coaches need more analysis to understand fully what happened.

Athletes either create propulsion (including starting RFD considerations) to project their own body or to propel another body (heavy) or object (lighter). Barbell information can show success later by relating to the athlete’s size and the demands of his/her sport. One can’t simply look at relative and absolute numbers anymore, as sports are becoming more and more competitive. Dissecting the repetition to more data points is valuable and worth the time.

These three simple examples should be familiar in any strength and conditioning setting.

- Body stature considerations – Peak velocity for a tall offensive lineman is much different than for a shorter and stockier defensive tackle. For example, Jonathan Ogden at a looming 6-9 has more time to produce a peak velocity as his limbs are long. Anthony “Booger” McFarland is reportedly 6 feet even, thus has less time to work with but likely has a great mechanical advantage for RFD. In view of their respective roles on the field, coaches want to preserve what makes them special and not expect everyone to have the same barbell performances.

- Load considerations – The 225-pound bench press for reps in the NFL may be outdated, but athletes are still expected to show up and perform. Because athletes are likely to score double digits, mean propulsion velocity matters because much of the rep is braking. With more maximal strength movements, mean velocity is just as valuable because maximal strength lifts are so slow throughout the repetition.

- Technique considerations – In my article about Barbell Displacement, I outlined how fundamental and sometimes advanced metrics can polish a great strength and conditioning program. Teaching someone full range or analyzing smaller ranges (competitive-style weightlifting versus power options) is a starting point, not a nice-to-have feature. A simple change in stance or grip can mislead progress or falsely show regression, so displacement adds perspective to peak and mean values.

More examples exist, but the point of the propulsion angle is to think about how athletes create forces with their bodies, style of technique, and use of time and space. RFD and peak velocity are likely the two best starting metrics while the mean velocity family and distance of the exercise connect the dots.

Does Mean Propulsive Velocity Deserve Discussion?

Unfortunately, most coaches are unaware of how both mean velocity and mean propulsive velocity are measured and why it’s important to know. If you are serious about weight training and utilizing VBT approaches, you need to know how mean and peak velocities are measured and why they are valuable. Some authors have questioned the value of peak power and force, but output is important in quantifying work done. Remember:

- MPV cuts out the deceleration or braking phase from light-speed lifts, a part that can distort the performance measurement of some lifts.

- MPV can be a part of both ballistic or non-ballistic exercises, but provide the most benefit to light strength exercises where nobody or bar projection takes place. When the load is heavier with strength exercises, mean velocity is still relevant.

- MPV is a great complement to specific RFD measurements if interpreted with great care.* MPV is also a great term to use while talking about barbell tracking because only the concentric action of the lift is measured and vividly illustrates how the measurement is taken.

* RFD is a general term describing the production of force from the first effort to peak muscular effort, and it is a wide territory for analysis. The time frames and how they are assessed are extremely important. RFD is a strong factor in performance but like any individual metric, the entire picture is needed for comprehensive evaluation.

How Mean Velocity and MPV Are Measured Scientifically

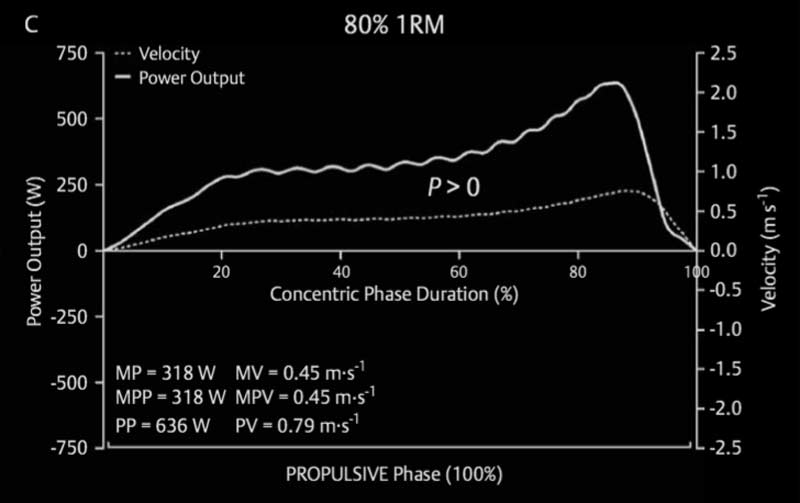

Figure 2. Coaches should look at wattage for power and spot check the velocities to ensure the exercises are done with the appropriate bar speed.

At first glance, it’s convenient to reduce an exercise to concentric or eccentric phases. The summary one sees in some texts of a weight picked up and dropped, pushed and lowered, is okay for explaining to the layperson what happens, but not enough to help athletes. Exercises have similarities and general commonalities, as well as unique differences. Most devices that measure barbell performance will record the concentric and eccentric motion, but the primary scores displayed are the concentric output only.

A velocity score on a tablet or smartphone shows a summary (average) or single (peak) velocity measurement. The problem with mean or average scores is that the sample range could include numbers that mislead or poorly represent what the user wants to know.

Concentric phases of strength lifts include a period of technique that doesn’t represent propulsive force—simply finishing the rep—and that is braking or decelerating. Mean propulsive velocity responsibly cleaves the deceleration component in strength exercises that is subject to possible technique discrepancies. By focusing on force production, coaches know what neuromuscular adaptations are happening versus what small nuances could be blinding the training scores. The researchers from Spain looked at light loads and found that Mean Propulsive Velocity has value with some instances, but the future will be still focused on minimum values as well as peak velocities.

In summary, the findings of the present study show the importance of referring the mean mechanical values to the propulsive phase of a lift rather than to the whole concentric portion of the movement, especially when assessing strength and muscle power using light and medium loads. We advocate for the preferential use of mean propulsive parameters since they seem to be a better indicative of an individual’s true neuromuscular potential. (Sanchez-Medina et al.)

The Spanish studies usually showcase higher rep ranges and this is why MPV is great for light or medium loads, but the study on strength assessment and the propulsive phase explains the pattern of how braking becomes less involved with heavier loads. Looking at MPV with high repetition strength exercises (10 reps or higher) is very limited, but could be something used with jump squats according to Loturco and colleagues.

Since jump squats technically require one’s entire body mass (including weight) to be displaced in the air, takeoff velocity and peak velocity can be confused. I have not seen how using an optimum power load is superior to a comprehensive program that holistically increases maximum strength and RFD concurrently, but the study authors make an interesting suggestion. Perhaps the newer metrics are not the end game in VBT but rather a hint that we still have a lot to explore and should measure as much as sanely possible to uncover what is driving what in sport performance.

Juggling Multiple Variables for Full Analysis of Barbell Performance

Bryan Mann’s book on VBT (Elitefts.com) outlines velocities of successive zones to create guidance within those zones. Mean and peak velocity are the two pillars to American coaches in general because of the Tendo system. But those are training metrics, not planning numbers. The purpose of the article was to ensure that the workouts performed meet the expectations of the exercises, not replace designing a good workout program.

Force, power, velocity, and even displacement are extremely useful variables but most coaches are familiar with the speed zones, and that is fine. If athletes perform the exercises in the vicinity of the intended velocities, the training plan has a chance. Force and power—be they peak or mean—have less connection to coaches because most relate to total weight on the bar, and speeds ranging from .3 to 2.2 meters per second. Coaches know when the weight is heavy, and athletes are battling in a squat, and when athletes are snatching fast when the reading is above 2.0 or similar. Barbell speed tracking is comfortable, but bar velocity is very much in exile unless the coach has other contextual numbers.

Here are some takeaway suggestions I have struggled with so you don’t have to waste time:

- Measure body composition as much as possible. Strength and any other ratios to bodyweight are never as valuable as getting the contributions of lean mass as well. Two 75-kilo athletes may perform similarly but succeed much differently. I like the direction of the concept of bodyweight percentage that Sparta shared in the article from Bryce, but they are only the middle point. Many athletes can squat 2 times bodyweight or snatch their bodyweight, but no magic coefficient shows up to explain why some outperform others with speed and jumping.

- Never isolate power numbers if conditioning matters in your sport. So many athletes look great in combine testing but for some reason struggle when aerobic factors are mixed in. Don’t compromise too much and learn how to balance both so performance is maximized on both ends. Conditioning or displacement rates in field tests should be combined with body mass and stature measurements. It’s fine to test speed and power separately, but watch how power fluctuates when practice and/or conditioning are added.

- Most coaches ignore power and force metrics, but it’s important to add those scores to the database of training records. Peak and mean values add more landmarks to what is going on, especially when the lift displacements are accurate. Instead of tossing the numbers out, watch how they trend over time. RFD, time to peak, and other metrics will give immediate and long-term guidance if analyzed and interpreted correctly.

- Again, make sure to perform speed and other field tests. If you have more weight training metrics than speed metrics, rethink the purpose of your training. I am amazed how many coaches will inventory massive lists of barbell outputs but barely hand-time sprints—if at all. I suggest making sure you record other field tests in jump performances with vertical and horizontal movements. The wider the range of tests, the less likely bias or style will hurt your program. Most coaches with distinct styles who showcase their programs are least likely to succeed because they should be reflecting athlete needs. If a colleague can read your workouts and easily see your fingerprints, it’s likely you are lost internally with a philosophy rather than what your athletes are showing physically.

Suggested Reading

If you don’t own Paavo Komi’s classic Strength and Power in Sport, I highly recommend getting it. Other texts such as Strength and Conditioning: Biological Principles and Practical Applications and Neuromechanics of Human Movement are gold as well.

Please share so others may benefit.

[mashshare]