The thoughts that inspired this article circulated around my brain for a long time. Working, as I currently do—or indeed throughout my entire career—in a multi-sport environment and interacting with a multitude of sports technical coaches, sports scientists, strength coaches, physios, nutritionists, and many other sports performance professionals, I have encountered the issue of “special” sports many, many, many times.

A vast number of these professionals have a deep-seated belief that their sport is special, different from any other. Special in that their sport and their athletes do not conform to the laws of human physiology, biology, chemistry, and physics. In the world in which their sport is contested the sky is not blue, the earth is not round, and our planet does not revolve around the sun. Speed is not speed, force is not force, and strength is not strength.

Their sport requires special attributes unique to that sport and they must train special muscle groups that only their athletes possess. They have no time or place for max strength, relative strength, power, and rate of force development. Coaches in these sports often are former athletes who had high—or at least moderate—levels of success themselves. They “know” what it took for them to achieve success, so they “know” how to get their athletes there.

Figure 1. An example of a “sport-specific” exercise with dubious benefits for performance.

That is a decent starting point. First-hand experience of what it takes to be a winner at the very top of the sport is something you cannot learn—you must have experienced it. That is why so many top tennis players in the world have former multiple Grand Slam winners in their entourage—Murray with Lendl and then Mauresmo, Djokovic and Becker, Federer and Edberg. Look at Pep Guardiola in football: world-class player and manager.

Figure 2: Pep Guardiola (left) and Jose Mourinho demonstrate that an elite-level playing career is not necessarily essential for coaching success.

But being a successful player, athlete or competitor is not necessarily a predictor of a successful coaching career. For every Guardiola, a Jose Mourinho (with no footballing career of note) is equally accomplished.

It is often said “a week is a long time in politics,” and time passes at an equally rapid rate in sport. What was relevant to an athlete who played 10, 20, 30 years ago—as may be the case for many current coaches— may now be consigned to the great training graveyard. Football managers no longer (except maybe the bad ones) have their players running up sand dunes until they puke. The world of elite sports performance has come a long way since the 1980s and 90s.

Part of this increase in performance levels is due to the rise of the profession of strength and conditioning. The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) was founded in 1978, ASCA (Australian Strength and Conditioning Association) in 1992, and the UK Strength and Conditioning Association in 2004.

Another aspect is a corresponding rise in sports science. One of the greatest coaches in sporting history, Sir Alex Ferguson (manager of Manchester United 1986-2013), said “sports science, without question, is the biggest and most important change in my lifetime.” 1

Figure 3: Sir Alex Ferguson, arguably the greatest football manager of all time, recognized the importance of sports science in modern sport.

Ferguson was in his early 30s when he began his coaching career, and he retired nearly 40 years later. He understood the importance of changing with the times. Much as his teams, his players, and his club changed and evolved to compete with his rivals at home and abroad in the Premier League and the UEFA Champions League, so did Ferguson. His willingness to change resulted in his rightly being credited with producing at least three separate great teams at Manchester United. The message here for all coaches is that what worked before will not necessarily work again in the future. You must be open to new ideas and new information.

Figure 4: Not everyone respects the role of strength and conditioning. Andrea Pirlo (World Cup-winning footballer) said that the pre-match warm-up is “masturbation for conditioning coaches, their way of enjoying themselves at the players’ expense.”

Researchers from Edinburgh recently investigated the experiences, opinions, and perceptions of the usefulness of sport science support and knowledge of UK coaches among four different sports (football, rugby league, curling, and judo) and three different levels (elite, developmental, and novice) within each sport. 2 Perhaps surprisingly, there was more variation in perceived value of sports science between coaches at one level than coaches working at different levels of sport. The implications are that sports scientists and strength coaches need to do more to develop buy-in from coaches and athletes and that NGBs need to do more in terms of coach education in sports science and related fields.

There are good and bad coaches at all levels, and it is not necessarily the coaches at the highest level who are open to different perspectives and ideas. The research indicated that some coaches’ attitudes are shaped by prior negative experiences with sports science and other support staff. You may have to work against such negative attitudes and change the philosophy in your employment situation.

Good strength and conditioning coaches and sports scientists know their limitations. They are part of the support staff and wouldn’t dream of telling coaches how to deliver technical or tactical advice to players, except in certain circumstances where there is crossover between the physical capacities developed by the coach or scientist and the sports-specific applications of these capacities. For example, there may be a certain amount of crossover in delivery of speed and agility sessions.

You don’t always see the same respect for the strength coach’s knowledge, skills and experience. Despite having no greater qualification than their own training experience, many coaches feel they are qualified to dictate the minutiae of the program to the strength coach. Many skills and technical coaches don’t hesitate to tell S&C coaches what they should be doing, how they should be programming, what exercises they should and shouldn’t include. Some athletes even share this disdain.

Good strength and conditioning coaches and sports scientists know their limitations. Share on XThere, of course, needs to be a full and in-depth discussion of the needs of coaches and their athletes from the strength and conditioning program. This discussion should most often be centered around the big picture—the outcomes.

Respect of knowledge and abilities should run both ways. Strength and conditioning practitioners would never presume to tell coaches how they should coach their athletes, how they should play a forehand, spin a rugby ball, employ a certain tactic, and so forth. By the same token, I am bemused when I see coaches telling the strength coach that certain exercises should not be included because they make their athletes slow or some other spurious and misunderstood claim that belies a lack of knowledge about specificity of velocity of movement or any other number of scientific principles.

So, what can you as a strength coach or sports scientist (particularly if you are new to the industry or your present position) do to get respect and buy-in from coaches and athletes? First and foremost, spend as much time as you can with coaches and athletes in their environment. Delivering S&C for athletics? Get out on the track. Working in team sports? Be present on the field. Coaching rowers? Spend time on the water.

If coaches feel you have a strong knowledge of their sport and its demands, they will be more likely to listen to you as the expert when it comes to strength and conditioning. If you watch the athletes in their training, discuss what you have seen with the coaches, watch videos, and read books and other resources, you will not only have a far deeper understanding of the sport but also command more respect from everyone involved with the program.

This concept is well-recognized by sports scientists in their research and heavily promoted by sports science bodies such as BASES (British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences). “It is essential that sports scientists understand the needs within a sport fully before applying their specialist knowledge,” 3 note the authors of one study. “Issues around effective integration need to be raised. Support staff need to be afforded the time to gain acceptance and understanding as well as a willingness from coaches and athletes to facilitate the process,” 4 adds another..

Strong relationship-building between yourself as support staff and coaches and athletes is essential to facilitate this process. In the research and at a strategic level, NGBs and sports science bodies recognize the need for regular dialog and the effective application of specialist knowledge. At the individual level, you as a coach can enhance this process by following the recommendations made above: spend as much time as possible in the arena observing athletes and the sports’s demands, and conversing with coaches.

In some environments, these steps may be mandatory as part of the entire training process. Sometimes, however, you may be responsible for multiple athletes, squads, and sports, so attending all sessions is not possible. In these scenarios, you still need to get out and view the on-field sessions whenever possible. If a sport is novel to you, even spend some time playing it. Get a feel for what the athletes feel when they play and the demands of their discipline. Show the coaches you are interested, enthusiastic, and willing to learn.

It is not just support staff who must be willing to learn, though. Working in performance sports, every interaction with another coach, athlete, physio, or sports scientist is an opportunity to learn and grow. I have spoken with elite coaches with many decades of experience who remain open to new concepts. In this same vein, technical sports coaches should be open to the ideas of the expert strength coach or sports scientist they have employed. A coach stubbornly sticking to outdated principles that “served them well” as athletes may result in their athletes overtraining, becoming injured and winding up tired and disillusioned with their sport.

In many instances, coaches and athletes are not simple. Many coaches want fancy, clever, complicated, and advanced training techniques when their athletes have not demonstrated decent baselines in various athletic measures. But it is a lot harder to sell “doing the basics well” than a gimmicky piece of equipment, training method, or “sports specific” exercise. Coach Vern Gambetta has a great article in which he outlines several excellent training principles. Four in particular are appropriate here:

- Start with the basics and never stray far from them.

- Don’t try to replicate the stress of the sport in training. Instead, prepare for the stress of the sport.

- You compete the way you train. Understand the demands of the sport and train to exceed those demands.

- Don’t try to replicate the game in training. Distort it.

This article is a great reference, not just for strength coaches and sports scientists, but for all coaches and individuals involved in athletic performance training. Coaches need to understand that the weight room, or S&C training, is a place for athletes to develop a bigger engine than their sport demands, so they are more than capable of meeting and exceeding these demands. It’s a little like driving a Ferrari for grocery shopping or taking the kids to school. If performing different movement skills in your sport places a lower demand it you will be able to recover quicker, work harder, and beat your opponent to the ball.

Don’t replicate the stress of the sport in training. Prepare for the stress of the sport. - Vern Gambetta Share on XCoaches should not try to replicate the stress of their sport in training. They should not try and replicate the movements of the sport precisely in strength and conditioning sessions. S&C sessions should be used to prepare for the stress of sport and to exceed its demands. You shouldn’t mimic the game in training but distort it. Challenge your athletes to reach strength levels above those needed for the sport. Challenge fitness demands in team sports with examples such as small-sided games on restricted pitches. If you are training maximal velocity, utilize long rest periods, low volumes, and exceed distances and speeds commonly seen in the sport. Then sprints and agility will be at a relatively lower percentage of their max.

It appears that some sports are slower to embrace the ideas of modern sports science and strength and conditioning, while others have a greater respect for the need for specialist knowledge and skills. Rugby, for example, appears to have a much better attitude to strength and conditioning than football even though the latter is probably the world’s most popular game and far richer than its egg-chasing cousin.

This training video featuring Atlético Madrid preparador físico (fitness trainer) Óscar “el Profe” Ortega gained a lot of notoriety amongst the sports science and strength and conditioning communities a few years ago when it was promoted in Spanish media. The goal of physical preparation in football or any sport is to improve athletic qualities that will transfer to the sport. It is highly questionable whether this circuit training would benefit Atlético Madrid players’ physical qualities as displayed on the pitch.

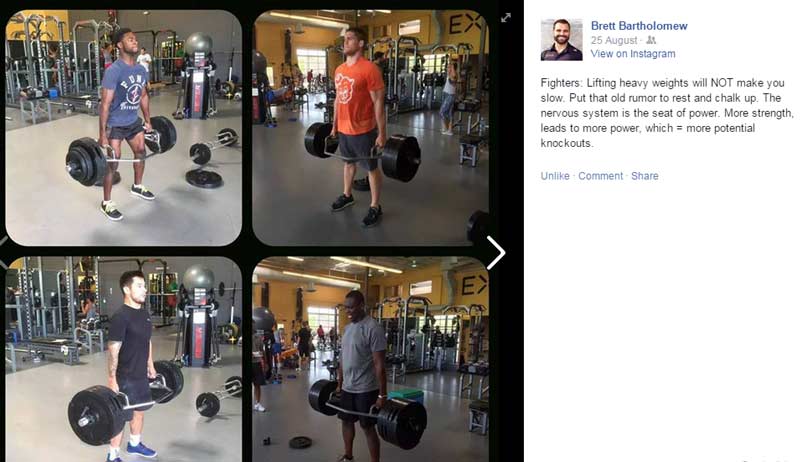

In my limited experience, sports such as the martial arts and others appear to have a terrible approach to sports science. Many coaches and athletes still believe strongly in old school training methods—millions of pushups, sit-ups, and long runs. Yet guys like Brett Bartholomew at EXOS and the guys at Boxing Science who work with World Welterweight Champion Kell Brook, among others, in the UK are fighting the good fight.

The messages should be clear. Everyone involved with athletic performance and development has something to bring to the table, but we need to listen to the experts in each area when they talk. Be open to new ideas. Novel ideas from coaches, strength coaches, and scientists may have something to offer. It may not be a new idea, but it may be new to you. The way you as a coach developed and earned your success as an athlete may have worked for you, but it’s not the only way. Superior and novel methods may now be available to you and your athletes. Remember, coach, your sport isn’t special. Stick to the basics, do what works, and do it well. Consistently.

Please share this post so others may benefit.

[mashshare]References

1. Sean Ingle, “Rise of sport science cannot hold back sands of time for footballers.” The Guardian, March 23, 2014.

2. R. Martindale and C. Nash, “Sport science relevance and application: perceptions of UK Coaches.” Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(8) (2013): 807-819.

3. A. Martindale, and D. Collins, “Professional judgment and decision making: The role of intention for impact.” The Sport Psychologist, 19(3) (2005): 303–317.

4. M.A. Pain and C.G. Harwood, “Knowledge and perceptions of sport psychology within English soccer.” Journal of Sports Sciences, 22 (2004): 813–826.

Hi Chris,

I have been looking for a long term development program for kids from 6 to 18 with little success. I have been out of sport for a while and have missed the changes in the last 15 years, particularly around strength and conditioning and nutrition.

I am concerned with the demands I see on children playing multiple sports where they and their parents are left responsible for deciding what is enough as coaches operate in isolation, each demanding of players.

As a coach, I’d like to ensure the kids under my care have a good physical, nutritional, psychological, tactical and technical grounding and are primed to play whatever sport they choose into adulthood.

I know children develop at different times and rates, but would you have any broad guidelines as to what they should be focusing on and when and what the recommended limits are at each age.

Thanks

Anthony