By Ken Jakalski, Head Track Coach, Lisle High School.

Research confirms what coaches believed all along.

Years ago, my coaching colleagues would hear me make statements similar to the following:

- The fastest “runners” in the world—cheetahs, antelopes, and quarter horses—do not need to have a running technique taught to them in a conventional human motor control sense.

- The emphasis on motor control is considerably overdone. Horses hit the ground running. Do they learn this via mechanics cueing as they drop from their mothers’ wombs?

- Horses, big birds, and virtually anything that runs and has been studied conform to general mechanical and energetic patterns, and all the experiments implementing deviations from those

patterns indicate that function is compromised.

These reflect some of my thinking relative to human and animal locomotion going back to 2001. However, as Dr. Mike Young notes, “Sprinting is an extremely complex motor task involving repeated rapid “switching on and off” of practically every muscle in the body.”

He’s exactly right.

Sprint Mechanics

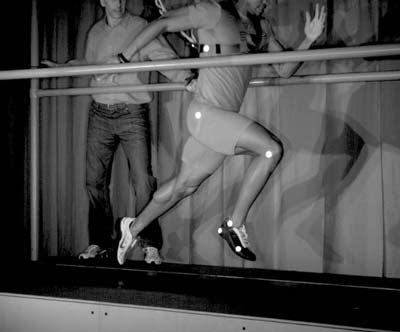

Sprinting mechanics can be developed in those athletes who do not already exhibit optimal technique. Mike Young said this over seven years ago, and recently, some excellent research out of the SMU lab corroborated his point. Some of the sprint drills that coaches have employed over the years may not have been the best means for developing technique, but this doesn’t mean their pursuit was unjustified. We simply needed a better handle on what exactly is happening on the ground at these high-end speeds. And now we know. The work of Ken Clark, Laurence Ryan, and Peter Weyand (Are running speeds maximized with simple-spring stance mechanics?) points to something very specific about the way that elite sprinters are applying force to the ground. Their forces are peaking much earlier in the stance phase than peak forces for their slower counterparts. This indicates that, in order to accomplish this, fast sprinters are applying large amounts of force in the right direction at the right time by way of a very distinct motion of the limbs in the “wind-up and delivery” prior to ground contact.

It is true that we don’t teach horses how to run, or babies how to walk, but fast runners need to execute specific movement patterns in order to make high speeds possible within the constraints of reduced contact time. Elite sprinting is indeed a horse of a different color.

Keep it Simple

Young often mentions the importance of having a general technical sprint model that is simple, flexible, and easy to administer. Through training, that model then becomes automatic in the sense that it requires little cognitive effort to produce. As he concludes, “If an athlete is either deviating from the technical model or having to think consciously to achieve that technical model in competition, the results will be less than ideal.”

So how do I reconcile my opening comments, considering that every knowledgeable coach agrees with what Dr. Ralph Mann said over thirty years ago: “sprinting is an unnatural activity”?

I can’t. But my hesitation to accept a variety of teachable skills was based on simply not knowing for certain which of those skills—as well as the cues for executing them—could be linked to the ground forces essential for top-speed sprinting. And though the merging of kinematics and support force data was something Dr. Young was suggesting over seven years ago, it wasn’t until quite recently that we had solid evidence pointing to specific mechanics that are both essential and trainable in the process of building what he describes as a “bigger engine for speed.”

But my caution over what skills to teach, as well as how best to teach them, appears to be somewhat warranted. Another key figure in the getting us closer to being right on these speed issues has been Dutch coach Frans Bosch. Bosh believes that we have two separate learning systems at work. One is conscious control via memory. That works best when actions must be performed consciously and without concerns about time. The other is an unconscious or automated control. That system works best when quick action is required in a more complex environment.

“Certain movements,” notes Bosch, “require split second responses and a flexible, highly efficient performance structure. A top-down central command system would not be able to do this accurately in sports because of the amount of information that needs to be processed and the speed at which this processing needs to be completed.”

Mechanical Interventions

But what are the implications of automated control relative to the mechanics interventions we make in our effort to help athletes run faster?

“However shocking this may seem to most coaches,” he says, “the better the practice result at the end of the training session, the less the athletes may ultimately learn.” He believes there are situations where practice results and learning results can be what he describes as “antagonistic.”

As a result, he feels that instructions that activate the working memory should be avoided. He gives very specific examples of this—things that coaches often give as what they consider to be helpful advice–such as “keep your elbow bent longer, extend your back before you apply force, and maintain pressure on the ball of the foot.”

Mike Young notes that there is indeed a difference between what we “see” in sprinters and what we should “say” to them, and he agrees that too much feedback should be avoided, especially when cues are not “clear, concise, and concrete.”

Bosch contends that eighty-five percent of coaching instructions are of this kind and are unproductive. “With simple movements,” he notes, “merely giving athletes encouragement is more effective than giving them internal –focus instructions on how to execute those movements.” Young concurs, noting that he also decreases the feedback over time.

High-Speed Treadmill

So, in a sense, what the locomotion folk were suggesting almost fifteen years ago does seem to make sense relative to what Frans Bosch is saying: “In order to give self-organization a chance, a coach must know what components to teach with precision and what components need the freedom to vary in exercises. A coach should not correct every flaw he or she sees; rather, the coach should have a list of the essential attractors and try to help the athlete get those right.”

The good news is that the current research out of the SMU lab has now given us a much clearer idea of what should be taught. And what is even more interesting is that these mechanics are not anything new. As Bosch frequently notes, they are the things we know will optimize the efficiency of the sprinter’s mechanical properties—things like posture and frontside mechanics. And with the knowledge that they were right all along, coaches can continue demonstrating what they do best—knowing how and when to teach these skills.

And this requires…more than horse sense.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

I agree. Sprinting can’t be over coached. The most effective cue that has worked for me is “run for your life”