By Carl Valle

My recent article about Boo Schexnayder attracted more than a thousand readers in record time, and is now a primary resource for coaches here on Freelap. During the past decade another amazing resource, Pierre-Jean Vazel, has become one of the major hidden geniuses in the world of athletics. His insights and statistical knowledge about sprinting are unmatched.

The Story of the Sundsvall Windsprint Seminar

I met P-J, as he is often called, during the summer of 2008. I had the honor and privilege of presenting some of my best regeneration findings at a small seminar in Sweden. I learned and shared some great information with the wise coaching legend Hakan Anderson and other European coaches. It was a true wakeup call, as their balanced views on training in the realm of strength and power are more progressive and less reliant on talent than here in the US. Pierre-Jean’s detailed hour and a half presentation had some information needing to be expanded for those less familiar with his work. I’ve updated and clarified the notes I took at that time.

Figure 1. One of my favorite examples of a professional is Stefan Tärnhuvud, a 100m sprinter who has put in the hard work and represents the sport the right way.

The purpose of this article is to preserve invaluable information that needs to be shared with coaches of all levels. Athletics is a wonderful example of art and science being performed on the world’s biggest stage. While perhaps a cliché, the reality is that coaching athletics is pure with the honesty of the clock or measuring tape. I hope you will find this information enjoyable and practical for your athletes.

Stride Development in Elite Sprinting

Throughout coaching history, numerous attempts to break the sprinting stride into simple groupings of frequency and length have created considerable misinformation, such as the myths that frequency is genetic and length is weight-room specific only. While some truth of absolute limits may have talent and strength interactions, the reality is that both qualities are likely to be developed by good coaching. While it’s artificial to break a sprint cycle into frequency and length in training, the value in doing so is to see what type of sprinter athletes are and what they need to do to maximize their potential.

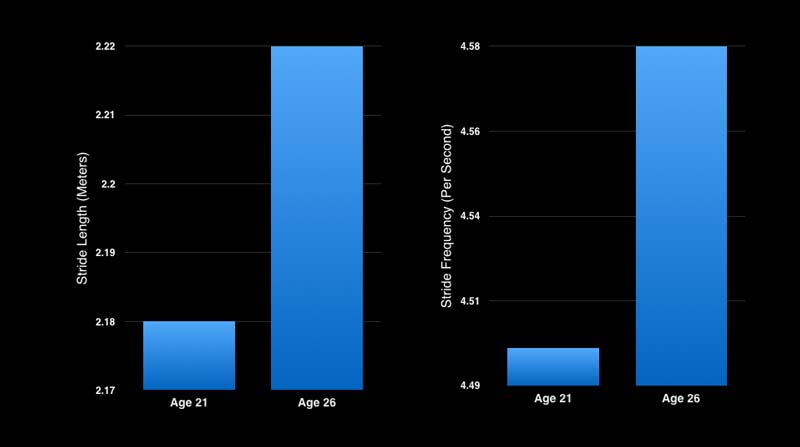

Figure 2. Small but significant changes in stride development with both length and frequency happen over the years. I learned how to drill down to a single stride and see what areas in training can help transfer to ground reaction forces.

Development of the stride cycle requires a complete understanding of the course of an entire career, not a knee-jerk reaction to exercises or drills. Often a new modality will create false hope of what might lead to a rapid evolution of ability, which we often see with some crazy exercises and foolish approaches. In his presentation, P-J shared a lot of charts and graphs of changes to athletes in ways they improved over the years, not just time slopes. Coaches need to use the information of stride parameters and be cognizant of the ways athletes improve.

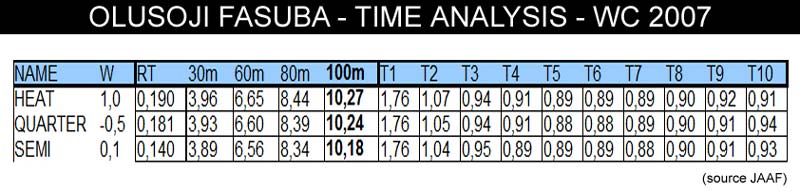

I found it useful to see how elites improved with awareness of the combination of their body type and stride style. After P-J shared his annual plan as well as his career work with African 100m recordholder Olusoji Fasuba of Nigeria, he delved into general discussions regarding sprinters. This is where things got interesting—the breakdown of how sprinters realize their genetic potential, and the trends and patterns that occur because of their body types and stride characteristics. P-J proposed that athletes have a relationship between stride length and body height. In fact, it almost seemed like a golden ratio of sprinting that one would eventually break 1.2 or more of their SL/BH. After knowing the ratio with elites, coaches must be aware of what is needed in order to achieve such standards.

Figure 3. This chart is redesigned from P-J’s original chart to show key variables like stride frequency and length, body height (in cm) and body weight (in kg), and composite scores such as SL/BH. It is a good example of how athletes develop over the years. I am in the process of updating it for other athletes and faster performances.

From P-J’s graphs (not pictured), it looks like both stride length and frequency improve concurrently, yet the real improvement goes to the less developed quality. The real question is not why this happens, but what specific efforts in training balance stride parameters for better performance. Another question is whether improvement comes from just getting years of racing and general training versus efforts to directly improve the weaker quality. The amount of notes necessary to reveal how athletes improve requires a lot of data in both training and performance.

When discussing stride mechanics P-J didn’t get much into drills as he was very open about not knowing if they worked or not. I interpreted that to mean no clear evidence pointed to what was going on. I concluded that drills are specific actions that could bias stiffness, muscle recruitment, or and/mobility of the stride.

Drills are potential diagnostic tools and ways to increase the motor learning “sponge size” of the athlete. Share on XWhen he discussed the stiff-legged prancing drill as one that could have an influence, I thought drills were just categories of locomotor phases that exposed sprinters to motions outside their comfort zone. I have spent years teaching drills because I feel that athletes need to “learn to learn.” General exercises during a warmup are more than just burning time and getting hot. Drills are potential diagnostic tools and ways to increase the motor learning “sponge size” of the athlete.

P-J was especially vehement that there is no such thing as “French Training Methods,” as no organized structure of training or unified training philosophy exists in France. Yet the most successful coaches and scientists have made a massive impact on the training world from a global perspective. For example, Jacques Piasenta is not “the” voice for France, but his international stable of athletes must be recognized.

P-J also touched on the theme of stiffness. The polish bench, a Russian box with sagittal plane emphasis, is one of many devices Piasenta uses to help with the lower limbs for proper transmittal of forces. Other exercises with weighted vests are multidirectional as well, confirming my suspicion that he builds massive stiffness for his athletes.

Adjusting to Chaos

Pierre-Jean spoke in fantastic detail about his work developing Fasuba. P-J’s training can’t be considered ordinary, as his attention to the daily tasks of training is very precise. At first, the training seemed way too simple to work, yet it often had to be that way because the circumstances were often in turmoil. Poisonous spider bites, workouts in parking lots next to soccer stadiums because of venue limitations, witch doctor tea drinks, and cold indoor training centers in Paris were all reality. His stories of daily circumstances provided vital documentation of the painstaking recording of the context of training. Workouts without the background story are literally only half the information, so I never send workouts alone anymore.

One of P-J’s important lessons was keeping detailed logs to share the metadata of training and competing. Everything should be placed into accounting, or the numbers are meaningless. Many times athletes will have false peaks and poor performances that are actually indicators of early tapers or good training hit with poor circumstances. Often training is changed for the worse because the results are not indicative of good training and the coach and athlete simply needed more time. I have changed my training protocols many times simply because I thought I was not doing the right things. If I had had more trust in the process, maybe something could have worked.

In reality sometimes life will be a stronger element influencing performances than a magical workout the week before. What I thought were excuses were in reality just honesty that sometimes life gets in the way of good training. It’s important to know the difference between explanations and excuses. With enough seasons, one knows what the real problem is—be it the coach, the athlete, the environment, or many times a combination of factors at the wrong time. While performances indoors may appear more consistent because weather does not play a major role, the reality is that many coaches will need the story behind the story to see the fruits of their labor.

Relationships and Athletes

At midpoint of the 60m final at the 2008 World Championships, Fasuba’s calves were cramping but he didn’t panic. He ran the exact same time in the previous heat (semi time of 6.51) with slight cramping. The lesson learned was that he was capable of a 6.4 but mustered another 6.51 under adverse circumstances. When your training is going well and your training times are good, you are bound to have a performance that demonstrates that ability.

Figure 4. The OHB or overhead back throw with a medicine ball seems to be an interesting test as it shows the best relationship outside the actually running speeds. Here one makes a good argument that athletes who can coordinate more muscle groups with the time frames of a behind-the-back throw are the most successful in the long run.

The lesson is that meets are all relative based on the context of the situation. The beauty of coaching is not the art and science, but the human side of working with people that makes all difference. While P-J may be known primarily as a statistician with times and splits, his relationships with his athletes are more than just numbers.

Many coaches tweet about “building trust” or “bonding” and then boast a week later about training 400 or more athletes. I think small training groups extract more information than larger, superficial pools. Let’s face it—it takes time to truly know people and offseason training for a few months is not my idea of fostering a connection with someone.

Elegance in Design

When you can’t deliver ornament, you have to deliver substance. – Paul Graham

My biggest concern about elegance in design is that training will be misinterpreted as easy solutions to the challenges of developing speed and timely performances. In reality, a simple solution is often a concise decision from a complex scenario. I am fearful that someone would interpret the summary below as a simple formula to success, when the truth of the matter is that the information is just a representation of the primary decision-making.

Figure 5. The calendar is the most straightforward way to represent results. The building blocks can always be split into more granularity, but a basic summary of how one achieves good performances is what I find most enlightening.

During his presentation, P-J shared his training outlines as well as other graphs that provided a nice summary of what he was trying to accomplish with his athletes, specifically Fasuba. I liked his reductionist approach and he often explained his rationale to what might be considered strange decision-making. A primary example is his weight training work with Fasuba. It could be considered very primitive in architecture, as it demonstrated no intricate periodization. I believe that what seemed a weakness actually became a strength, as his numbers were not unimpressive or lacking.

What I like about the summary of information is the absolute records and clear characteristics of what his athletes could do. In the latter part of his presentation P-J compiled his collection of data about the abilities of ultimate performance in the 100m and what was needed on average for a sub-10 performance. While I can’t verify those numbers are 100% accurate, I believe these power and speed values are created by the work on the track.

The hardest lesson I have learned is that speed training is activation training at its fullest. I believe sufficient loading and mechanics can create a massive recruitment of HTMUs (high threshold motor units) when sprinters are competing heavy or sprinting fresh.

Individualizing Training and Finding Ways to Improve

One conjecture I looked at was P-J’s explanation of Fasuba’s ankle restriction and how this could be indirectly related to some factors in exercise selection with his squatting. Simply measuring ROM with a goniometer is not going to solve specific metatarsal patterns as well as unbinding of soft tissue problems in lower limb musculature.

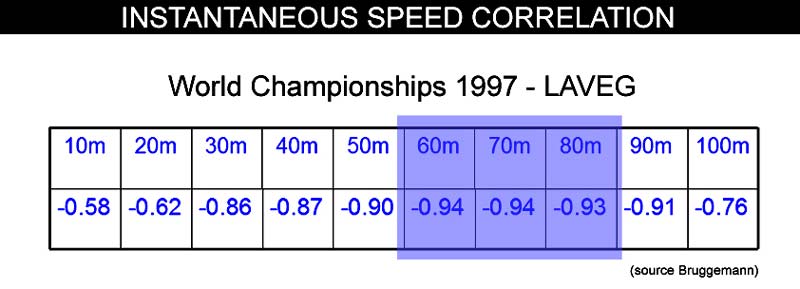

During my questions with P-J, it seemed to me that elite sprinters could make big improvements in the later zones. While top speed has improved slightly since Carl and Ben in the 1980s, my interpretation of performance gains is the string of consecutive splits at near-top speed.

With the impressive performances of Powell, Gay, and of course Bolt, I feel the advances reflect whole races being done instead of having the classic good accelerator or top-speed sprinter. My guess is that while many programs differ, the similarities will be closer than we believe. In the original forum review, I coined short to long and long to short when classifying the different approaches between Charlie Francis and Tom Tellez—with grave consequences.

Figure 6. Modern sprinters are now in 9.7 and 9.8 territory, mainly because all phases of the event are solid. No more good starters, no max speed guys, and no closers. This era is characterized by no weaknesses and not relying only on strengths.

For a decade people felt two distinct systems of short to long (S2L) and long to short (L2S), when in reality they are just two examples and most successful programs do something in the middle.

No program is pure, as a long to short program will have episodes of start work with accompanying acceleration regardless of the intent of the phases. Plyometrics and weights may be more intensive, creating a running program with some interesting composites. Even if a program utilizes extensive tempo, a running speed at 75% is getting ground contact times with stiffness qualities that will have indirect maximal elements even if the loading is considered aerobic.

Figure 7. It is interesting to see how Fasuba got faster in each round. Even when athletes are injured or not performing at their best, one can learn how various elements interact with time on the splits.

I don’t know what to use as an example of what humbles me more. One good story is the description of Fasuba’s fourth-place performance in the 100m. While his 10.07 in the final was not earth-shattering, P-J’s true wisdom was that like all outstanding coaches he used his observation skills. After each round Fasuba got up from a seated position from the ground easier and quicker, barely perceivable to the naked eye. This makes me wonder if those who are slaves to fancy gadgets are hopelessly lost in understanding sport performance. I am a huge proponent of technology, but even so I always like beating the computer with the human element. Every coach likes being a “John Henry” and beating the machine.

Closing Thought—Observation Trumps Everything

One of Piasenta’s books on training is titled Aprender a Observar—Atletismo [Learn to Observe—Athletics], a hint to all of us that sometimes it’s better to look a little more closely than to talk. I think those who share their observations are the best coaches, versus the ones who share what they do coaching-wise. Most of the success I have observed is trying to see what others see, and currently I see a rise in people sharing what they know or what they tell their athletes with cues and other coaching-centric approaches. Athletes need a guide or a scout, not a babysitter or overzealous instructor. The less egotistical the coach, the more their words work as each statement is precious, not noise.

Please share so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

you have to subtract reaction time to find true frequency

What does the “D” column represent in the 100M Stride Parameter chart?

D for Density: 1000 x Body Weight (BW) / Height (H). The column -may- indicate that Tyson, Tim, Frankie and Francis should have bulked up, and that Bruny should have slimmed down.

How do we measure stride length

Where can I contact a fast sprinter that can coach me?

how fast ??

Stride length is discussed, however I’m pretty sure its step length even though both can be labelled SL