Mladen Jovanovic is a physical preparation coach from Belgrade, Serbia. He has worked internationally with various clubs and teams and is one of the leading minds in sport training. His knowledge of both science and technology is very impressive, and he really has a great grasp on training theory.

Coach Jovanovic was involved in physical preparation of professional, amateur and recreational athletes of various ages in sports such as basketball, soccer, volleyball, martial arts and tennis.

Mladen’s articles, interviews, articles, products and services can be found on his website at Complementary Training.

Using Moneyball Approaches to Data Visualization

Freelap USA — Over the years you have been interested in how data can help athletes. Perhaps the next iteration of Moneyball is helping coaches visualize practice and player rotation with reports. Infographics and data visualization have the potential to get everyone on the same page. What do you think is key in showing daily and weekly reports with practice? Who are good influences on aggregating all of the data in your opinion?

Jovanovic — Player rotation sounds good in theory, but I’m not sure how it should be implemented in practice. Saving key players for a more important game from a less important game might sound like a good idea for the club and players, but might represent troubles on the level of the league, especially if the result of that “less important” game is of high importance to some other club in the league. I am not sure if there are league policies regarding these situations, but IMHO they should exist so the clubs know what are their rights and obligations. More clarity as Patrick Lencioni would say (see The Advantage: Organizational Health Model).

I think data visualization is key in presenting reports to coaches since most of them are clueless on statistics — besides, a well designed graph can say a lot immediately. When it comes to designing graphs that tell you a lot, I always turn to Stephen Few. Some of his charts are very hard to implement in Microsoft Excel (which is the most widely used tool to store, analyze, and present data) though. Well designed graphs should be ‘easy on the eye’ and tell the whole story.

I also think that reports, besides presenting only ‘describe’ analysis, should also give more ‘prescribe’ analysis (in other words Predictive Analysis), or something that it is not immediately evident. Similar to a physical testing approach.

One simple approach is ‘tagging’ periods in training — this way the coach can know how much he spent on certain quality and how that aligned with the objectives of a given period. For example, specifying that the team is working on an offensive transition, but spending a lot of time in possession games and set-pieces.

Carl’s take — Every year my summer project is reporting for end of year evaluation of athlete care and it’s amazing the problems we see with medical and performance data being so difficult to consume, and the difficulty making everyone get on one page. One way I think this will change is the use of interactive and articulated timelines, something that tablets and interactive white boards will provide an easy way for those involved to problem solve.

Integrating Power Sensors with Player Tracking

Freelap USA — You have focused a lot of time on LPT (Linear Positional Transducer) data to make weight training more effective for athletes. Professional football clubs are in dire need of lifting changes, but programming and social culture impede evolution. What do you think is key for power development and soccer in helping athletes keep resilience and high output? What are you seeing in speed and power with good program design and LPT data?

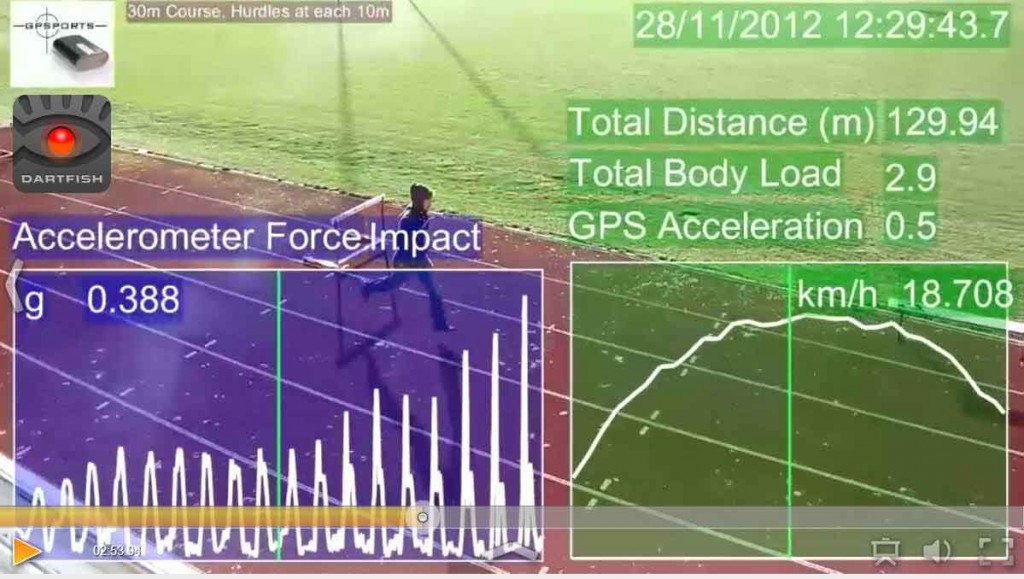

Figure 1: Data from GPS and activity tracking devices can be shown to enhance understanding of player speed and forces during real movements. Combining this with player testing is an emerging approach with sports teams.

Jovanovic — Not sure LPT is a solution to very needed cultural change. The solution might be the clubs’ board. What I mean by this is that when hiring a coach/manager, the board should also look, not only on prospective manager’s competition successes, but also his injury history and how many he ‘butchered’ along the way. Sometimes this (success and injury rate) is very much linked and there is great data to show that coaches switching clubs also bring certain injury profiles with them to the new ones (data from UEFA and Dr. Jan Ekstrand). If the coaches know they are being evaluated using injuries besides trophies won, maybe they will start to pay more attention to a good medical team, return to play programs and of course good physical preparation. We can talk all day about cultural change, but until their “balls” are not on the line, they will not care. In Serbia we have a saying that to kill a snake you need to hit in the head. In other words, to start the cultural change we need to hit in the head – on the top leadership. No amount of technological gadgets will change this.

As for LPTs, I haven’t implemented them in a degree that I would love, mainly because we only had one GymAware unit and three rack and the level of the players wasn’t demanding such an approach. Together with Eamonn Flanagan, we have written a practical review paper on how to use LPTs in strength training and it should be published in Australian Journal of Strength and Conditioning soon. In my opinion the implementation of LPTs in training can have a couple of steps and could be implemented depending on the team needs and level. The first level is simple feedback, especially with ballistic movements like bench throw, squat jump, snatch pull, jump&shrug and hex bar jumps. The second level is creating a load/velocity (or power) profile, especially in loaded and unloaded jumps. Third level is daily estimate of 1 RM (one rep max) using submax warm-up sets. This daily estimated 1 RM could be used instead of pre-cycle 1 RM (in percent based systems) since it takes variability of the strength into account. Fourth level is using velocity instead of load (%1 RM) to prescribe training ~ this is mainly done using start and stop velocity (see percent-based to velocity-based converter). Why this complexity, instead of simple %1 RM and reps, maybe RPE? Well, because velocity might be more ‘stable’ than 1 RM over a cycle, which means that if 1 RM changes (chronic change or daily variability/readiness), prescriptions based on 1 RM need to change as well. But, velocity associated with a given %1 RM don’t change much or at all (except when one with purpose tries to ‘shift’ velocity profile). Mentioned four levels represent solutions that slowly increase in complexity, but there is still certain things/principles to be validated in velocity based approach.

Carl’s take — Rugby and American football places more attention to the weight training and I believe basketball and soccer will start to realize that weight training will be the only way to reduce injuries provided that progression is very conservative. What Mladen has shared above is something I do with some clubs looking to implement better lifting protocols and the loaded jumping is a great way to develop power and monitor fatigue at the same time. Instead of looking for fatigue coaches need to embrace developing power. The suggestion I have is to rotate unloaded and loaded jumps with specific velocities based on profiling so one gets a training effect and fatigue pattern. Then the athlete can be directed to heavy loading if they are hitting benchmarks or directed to a more maintenance style workout. If the athlete is not recovering normally and is spending too much time in holding then a “person to person” intervention should happen to see if the athlete needs help with stuff on his or her plate. We need to stop babying athletes by looking for fatigue by showing the expectations based on what is possible when one is eating and resting properly, all provided the team coach isn’t trying to develop 4th quarter toughness or punishing people for going to Club Jaguar at 3 am.

Programming Conditioning for Team Sports

Freelap USA — Can you expand on your ideas about conditioning for sports and some of the work by Martin Buchhiet with MAS and how to improve this ability without interfering with power? Conditioning can be difficult to gauge since so many options in practice exist to support it or perhaps interfere. How do you see weekly sports such as NFL leveraging player tracking to get enough stimulus to stay fit without loosing sharpness for Sunday? What can soccer learn from football and what can football learn from soccer regarding conditioning and weekly set-ups?

Jovanovic — That’s a very good question. I think that the key is having reliable feedback or metrics. Without it we are just assuming a lot of things, especially since there is huge individual variation in reaction to training. The relationship with MAS and game/practice performance is also very complex. Improving MAS might yield more distance covered in a game/practice, and it might not. And also the distance covered in game/practice might represent enough stimuli to improve MAS. Anyway, without tracking both for players we are just assuming. In other words, we need to know if the current workload is enough to maintain and/or stimulate improvements and act accordingly. This again sounds great in theory, and in practice might be difficult to implement due to time constraints, etc. The goal is to know what physical qualities are players gaining or destructing from practice/games and complement that with general/specific physical preparation. This might be very variable. For example, older players might need removal of certain workloads to maintain performance or even availability. Sometimes too much of a good thing could be a bad thing. Again, having reliable feedback and acting upon it is crucial. These are the basics of cybernetics and automation in general.

IMHO, football can learn from soccer that certain aspects of skill acquisition and physical preparation could be ‘conjugate’ and that training environment could be a ‘live’, instead of closed “run here, turn there” drills. It can also learn that SKILL is king, not speed and certainly not strength. They are different sports indeed, and physical preparedness is a lot more important in football than soccer, but sometimes physical preparation in football can go overboard and represent training of powerlifters, strongman and weightlifters, while disregarding expression of that potential in a ‘live’ environment. On the other way around, soccer can learn from football that certain exercises should be ‘general’ for the overload to occur, and that not everything could be solved with playing with the ball. Some of the soccer coaches and players still believe that squatting makes you slow. I think soccer and football cultures are a bit on opposite ends of the physical preparation extreme and that they both need to ‘swing’ back to the middle.

Carl’s take — The next evolutionary step is creating a technical and tactical session that is seamlessly integrated with the physiological and biomechanical elements of sport science. I have seen a few weekly set-ups of NCAA and NFL football programs and it’s clear those that have coaches that understand fatigue and loading for sharp and crisp rehearsal are better than any strength and conditioning program that adjusts for coaches error in body loading. Nobody is doing this properly since every team has their pet data and weaknesses. Those that are interested in holistic and wide range of data will have the advantage, provided the team coach is eager to learn and has the ability to teach and train the team from practice design. Motor skills and sport skills are not the same, and practices after competition are hard to conjure outputs because fatigue and recovery periods are needed to practice at closer game speeds. The good news is that several teams are doing this on paper very well, and the coaches are doing a great job executing what is planned.

Motion Capture with GPS in Elite Sport

Freelap USA — Technology is merging with sport science and examples include motion capture and GPS. Where do you see the future with all of this going? Regarding gait analysis and foot mechanics, do you think in the future we will see more monitoring of muscle status (sEMG and muscle tone) and kinematics of motion under fatigue?

Figure 2: Skeletal Animation in Myometrics

Jovanovic — I think that the future is in how we analyze things and represent them to be meaningful. We already have technology to do a lot – but we lack analysis methods to make it meaningful. This is all my opinion of course. I think there will be decrease in technology and gadgets use since it is more burdening than reveling and couple of them will prevail that are valid, reliable, sensitive and easy to use. If the technology doesn’t give something that is ‘actionable’, but only descriptive (see the above descriptive vs prescriptive example) it will be of less interest. We still need both, but at the moment prescriptive is way underutilized (e.g. what does this tells me and how can I make actions based on it?). Some of the tools you mentioned might give us idea what should/could be changed (e.g. TMG, gait analysis), but I am not sure we know what should be done to change it. Of course having feedback is important, but I am not sure if we still have a proof that certain asymmetries lead to injury – but rather that injury lead to asymmetries, which is great for return to play protocols.

Carl’s take — Asymmetries are debated because sometimes athletes don’t get hurt with asymmetries and some do get hurt without them. My feelings are that we can learn from F-1 racing that the faster the car, the more likely it is to break down and the body can only compensate so much. Many athletes have asymmetrical areas but good fitness and strength can manage the problems by creating contractions to dissipate forces and adjust firing patterns. The problem is that only so much can be done before the body simply can’t handle things and if you have ever seen a warped frame of a car from alignment issues you can ask if structural damage is something that we should allow to the body. Great surgeons are amazing people but we need to ensure the forces on the body are not creating tears and damage with high-octane athletes. The body can only handle so much regeneration and compensation before something gives, especially with long seasons and short preparation times. My prediction is that the fusion between companies that provide volume and distribution such as Catapult and GPSports and movement solutions such as Myometrics are going to be the new oil for performance and medical data.

Speed Development on the Field

Freelap USA — Repeat Sprint Ability has a huge interaction with different variables and simple testing can illustrate when one is fit and when one is not. How do you evaluate if athletes need to worry about speed development if they are starting to age or get beat in games? Player tracking has a lot of variables and raw global speed is the backbone to many sport scientists looking at 10-15 m linear speed. What are your thoughts about player speed development in team sports?

Jovanovic — As always, skill is king. We have seen a lot of ‘slow’ players that were awesome due their skill levels. Those that need to worry are those who are not on the extreme of ‘skillness’. Speed is hard to develop (it takes some hard and smart work), especially in already developed athletes paying one to two times per week and with soccer it might be easier to recruit faster players.

RSS (Repeat Sprint Sequence) might not occur so frequently in a game, but frequency is not the same as importance. Someone might jump once in a game (and some lab coats might declare that jump is not important since, well, happened only once in a game), but he might over jump the defenders in the corner kick and score a goal. We definitely need to rethink our logic and biases (see Kahneman Thinking Fast and Slow). I am interested in something called Worst Case Scenario Analysis. One wants to prepare for those and we might miss them with our ‘averages based’ analytics.

To make soccer players do a good effort to develop speed we must take a bit different approach from traditional track and field approach. These guys used to ‘play’ and ‘compete’ so, pretty much everything should be form of play and/or competition. It would be hard for them (most of them) to give a good effort with 3x4x20 meter with 2 minute rest approach. But putting two guys on the ground and passing the ball into space towards the goal, might motivate them to give very hard effort (sprint) to catch it first. Besides hill sprints (which I really like, but not all clubs have hills behinds their fields), most of the speed work should probably involve a ball and play/compete element. Not because it is ‘soccer’ specific, but because it is ‘culture’ specific and they will buy into it more easily. Team sport athletes just haven’t grow up competing against themselves in training as T&F athletes. Hope this all make sense.

Carl’s take — Acceleration development can be easily trained with the use of timing gates and good sleds. The reason like sleds for soccer is that the pitch or training areas sometimes don’t have good hills and it’s easier to see speeds with unloaded sprints and other variables such as weight training, jump testing, and neuromuscular monitoring. Sometimes development may be preservation of talent, and coaches may be seeing who can keep the fast athletes fast, and make sure those that have room to improve doing something to get better. A few consultants focus on monitoring and not testing and this is a big problem. If one is not prepared to do a linear sprint or choreographed/reactive agility session for testing purposes, how are they prepared for a game? Also player tracking is context specific, and speed testing is very clear what someone capabilities are.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]