By Dr. Denny Kolkebeck, DPT, CSCS

Not too long ago, it was common to have kids who played football, basketball, and baseball; athletes who played soccer, swam, and ran track and field. They weren’t outliers or mavericks who eschewed formalized clubs and traveling teams that played year around, just athletes who possessed athleticism and a desire to express it every way they could.

Somewhere along the road, the “norm” became athletes choosing (or being cajoled into?) a single sport with a season that not only entails their school season, but nearly year-round participation in travel and club teams.

This growing trend hasn’t gone unnoticed. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) committee on sports and fitness has stated:

There appear to be increasing numbers of children who specialize in a sport at an early age, train year-round for a sport, and compete on an “elite” level. The lure of a college scholarship or a professional career can motivate athletes (and their parents) to commit to specialized training regimens at an early age.

Sometimes less is more… especially in the early stages of development. Share on XThe low probability of reaching these lofty goals does not appear to discourage many aspirants. To be competitive at a high level requires training regimens for children that could be considered extreme even for adults.

The ever-increasing requirements for success create a constant pressure for athletes to train longer, harder, more intelligently, and, in some cases, at an earlier age.

While it is natural and advantageous to have a competitive spirit and desire to maximize God-given ability, the growing trend of specialization to achieve these goals may have some negative results.

The Dark Side of Youth Sports

Loyola University Medical Center recently released the results of their study titled, “The Risks of Sports Specialization and Rapid Growth in Young Athletes.” The authors found two relationships among injured vs. non-injured athletes:

- the injured athletes spent more hours per week playing sports (19.8 hrs/wk vs. 17 hrs/wk)

- the injured athletes also spent more hours per week in organized sports (11 hrs/wk vs. 8.8 hrs/wk).

Among the injured athletes, 60.4% were considered “highly specialized” according to the study’s six-point sports-specialization score:

- Trains more than 75% of time in one sport

- Trains to improve skill or misses time with friends

- Has quit other sports to focus on one sport

- Considers one sport more important than others

- Regularly travels out of state

- Trains more than eight months a year, or competes more than six months

On the six-point scale, the average score of uninjured athletes was 2.75, while the average score of injured athletes was 3.49 (a score of 3 or more was considered specialized).

The lead investigator, Dr. Neeru Jayanthi said while the current study is preliminary, “We should be cautious about intense specialization in one sport before and during adolescence. Parents should consider enrolling their children in multiple sports.”

While a competitive spirit is natural, the growing trend of specialization to may have some negative results. Share on XThe AAP’s report, “Overuse Injuries, Overtraining, and Burnout in Child and Adolescent Athletes” found 50% of all injuries seen in pediatric sports medicine are related to overuse—the cumulative micro-trauma to a muscle, joint, bone, or tendon under constant unvarying stress without adequate recovery time.

The AAP’s report suggested the following to avoid overtraining and potential overuse injuries:

- Limit one sporting activity to five days/week

- One day off from all organized physical activities/week

- 2-3 months off from organized sport per year to engage in strength and conditioning and to refresh the mind and let lingering injuries heal

The report also spoke to the risk of burnout among younger athletes, which is an interaction of physiological, psychological and hormonal changes that result in altered performance. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Chronic muscle or joint pain

- Personality changes

- Elevated resting heart rate

Younger athletes may also experience:

- Fatigue

- Lack of enthusiasm for practice and games

- Difficulty with completing routine tasks

Variety is the Spice of Life

The benefits of younger athletes competing in multiple sports was reinforced in the concluding remarks made in the AAP’s report:

Well-rounded, multisport athletes have the highest potential to achieve the goal of lifelong fitness and enjoyment of physical activity while avoiding some of the pitfalls of overuse, overtraining, and burnout, provided that they participate in moderation and are in tune with their bodies for signs of overuse or fatigue.

Athletes exposed to numerous sports also have an opportunity to grow their total athleticism—imagine baking a bigger pizza which then yields bigger slices; improve underlying multi-directional mobility and stability in muscles and joints; develop and expand conditioning levels and express themselves physically and emotionally in different ways.

Input from Elite Coaches

Some college coaches also see the value in athletes playing more than one sport. In an interview, LSU football coach Les Miles said: “I’ve always enjoyed those guys that play all kinds of sports, all times of the year. They love to compete. There are some greater characteristics to those guys than there are with one-sport guys.”

When ESPN asked Virginia lacrosse coach Dom Starsia whether he preferred athletes to focus on one sport or multiple sports he replied:

It’s not a requirement to play multiple sports, but way more often than not our guys are multi-sport athletes and the best athletes at their school. They are competitive kids who do not want to sit around while other sports are being played.

I am always saying, ‘You learn to play lacrosse team defense and team offense on a football field, a soccer field, a basketball court,’ etc… I wince when a young athlete tells me that he is giving up football to concentrate on lacrosse. There is nothing you can do on your own that would be of greater advantage to your athletic development as a lacrosse player than going to football practice every day.

Former USC football Pete Carroll (currently the Seattle Seahawks head coach) once said, “I want guys that are so special athletically, so competitive that they can compete in more than one sport here at USC. It’s really important that guys are well-rounded and just have this tendency for competitiveness that they have to express somewhere.”

According to the article, Multisport Athletics: Why it pays not to specialize, over 80% of NCAA recruits did not specialize in high school. In the same article, professional basketball trainer Brian McCormick notes, “Cross-training through a wide spectrum of sports will enable teen athletes to experience multilateral development and increase their skills for success across the board of athletics.

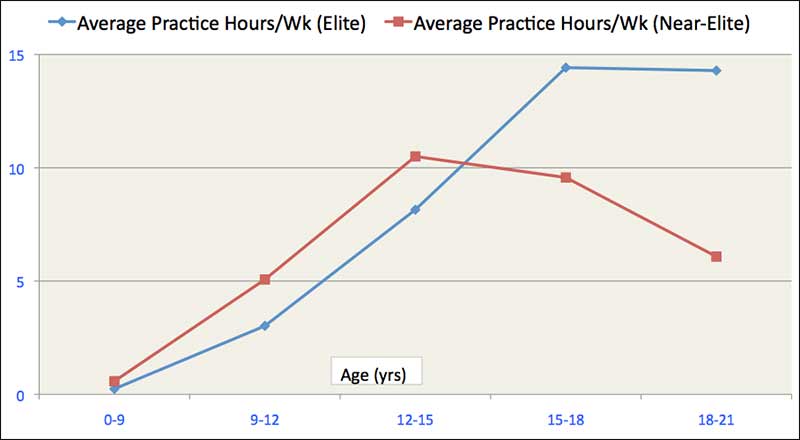

In the book, The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance, an interesting study was shared illustrating the difference in the average number of hours in practice per week “near-elite” and “elite” players spent during their early life.

The study found athletes who averaged fewer hours per week in formal practices until around their 15th birthday, had a better chance of becoming an elite athlete compared to those who practiced more before their 15th year.

Sometimes less is more… especially in the early stages of development.

Follow the Leaders

Numerous professional athletes have benefitted from playing multiple sports before making their presence known on the world stage:

- Soccer great Mia Hamm played football, basketball and baseball when growing up.

- Basketball star LeBron James played high school football.

- New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady was drafted by the Montreal Expos to play catcher before taking a football scholarship to Michigan.

- Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders both played professional football and baseball.

- 1980’s tennis star Bjorn Borg, who won 11 Grand Slam titles, played a multitude of sports and didn’t specialize in tennis until he was 16 years old.

- Basketball great Steve Nash played soccer in his early years and didn’t start playing basketball until he was 12 years old.

- In Jamaica, runners like Usain Bolt don’t start intense or specific training programs until their later high school years.

Slow Cooker Approach

Ultimately, the decision when and if to either specialize in one sport or play several comes down to parents, athletes and coaches collaborating to decide what is in the long-term best interests of the athlete.

The good news for younger athletes—especially under 12 years old—is time is on your side to get better; it’s not too late to start a new sport.

Coaches working with student-athletes would be doing them an immeasurable favor by adopting a “slow cook” approach to developing their skills and facilitating a “progress, not perfection” mindset. Encouraging athletes to take time-off and to play other sports would also be in coaches’ best interests since a mentally fresh and athletically diverse player yields better team results.

Plant seeds to bear harvest when it matters.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]Bibliography

Brenner, J. (2007). Overuse Injuries, Overtraining, and Burnout in Child and Adolescent Athletes. Pediatrics, 119, 1242-1245.

Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness. (2000). Intensive Training and Sports Specialization in Young Athletes. Pediatrics, 106, 154-157.

ESPN. (2010, Aug). Championship coach, Dom Starsia wants you to play other sports. Retrieved July 27, 2011, from League Athletics LLC and Braintree Lacrosse.

Epstein, David J. The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance. New York: Current, 2014. Print.

Hale, J. (2010, April 4). Multi-Sport Athletes: Why It Pays Not to Specialize. Retrieved Aug 6, 2011, from High Skool Kronicles.

Jayanthi, N., Pinkham, C., & Luke, A. (2011). The Risks of Sports Specialization and Rapid Growth in Young Athletes. 2011 Annual Meeting of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. April 30th-May4th, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Johnson, J. (2008). Overuse Injuries in Young Athletes: Cause and Prevention. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 30, 27-31.

Meana, R. (2005, May 26). Youth Soccer’s Dilemma: Is more actually better? (New Jersey Youth Soccer) Retrieved July 25, 2011, from New Jersey Youth Soccer Website.

STOP Sports Injuries Campaign. (2010, April 1). Young Athletes Overuse Their Bodies and Strike Out Too Early. Retrieved Aug 4, 2011, from American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

The Associated Press. (2011, May 19). Two-sport athletes flourish at LSU. Retrieved July 29, 2011, from New Orlean Net LLC Website.

Great article buddy. Good work