By Carl Valle

In the fantastic book The Science of Running, Steve Magness outlines a wonderful primer for endurance running, but it should just be seen as a manifesto on training in general. I have read the book six times already as every chapter is well written and practical. No one has found a way to take the science and make it applied in the endurance world more than Steve, and if I was on an island and had only a backpack of books this would be in it. As a sprint coach and someone who does a lot of monitoring reports for team sports, a few nuggets and gems can be lost as the pace he wrote makes the hundreds of pages a quick read. After reading it a few times, I wanted to share something I found underrated, meaning at first they are interesting and helpful, but they are perhaps instrumental. This book review is just the tip of the iceberg, and my interview earlier can’t replace getting the text. I suggest anyone training athletes buy it if you don’t have it now, and this is one of the few endurance books that can help sports teams.

What are the lessons? I picked five because of the Olympic rings, but one can get a hundred or more different nuggets of wisdom from his book. I found five I thought are hard concepts to understand and expanded on them as best I could. Very few people know that I spent a few years coaching endurance because the athlete was a monster talent that seemed to be slipping through the fingers of other coaches. I still remember and have all the data from his workouts and found my gut instincts ten years ago had the science to back up my heresy of training. Without getting on more tangents, here are the five lessons outlined.

Genes and Fiber Type

Hacking someone’s DNA is not cracking into some genome testing database but knowing how to target training beyond the cellular level to the molecular level. Steve illustrated his map of how to create a stimulus that leads to a functional change to the body and it was very well researched. In addition to genes, Steve talked about fiber continuum, and this is very important. Many athletes see themselves as some binary classification, such as fast twitch and slow twitch. In reality, an athlete falls in a continuum. One must realize that adaptation is not about conversion, but more remodeling from tissues being traumatized. Over time, bad training and aging simply decreases one’s Type IIX fiber and father time wins at the end with all athletes. So it’s not about defying one’s age or magic training programs, it’s who manages the decay better.

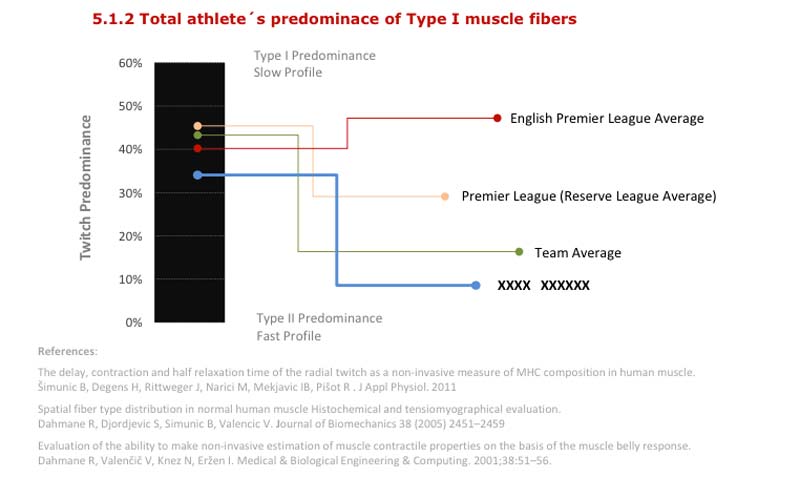

Figure 1: Above is a fiber type report from Haloview, showing not only the athlete’s explosive fiber potential, but also how they rank for comparison. Remember every rose has its thorn, meaning that someone who is explosive needs to be in great shape or they will fatigue faster. With less slow fibers available, conditioning is limited because only so much mitochondria can increase to the intermediate types. Don’t expect much from combined strength and endurance type workouts.

Gene translation and transcription are wrongly explained with many coaching analogies because one is not changing their who they are, just improving what one can be in time. Targeting genes is complicated, but it can be distilled to a simple choice of what is important and what training sends a clear message to the body. When people start getting fancy in training, it tends to be a mixed message of sorts. An example of this can be priorities in the weight room. When someone is lifting weights what is the adaptation we are looking for? Some coaches are trying to do endurance training to muscle fibers while they are in a weight room. True, secondary adaptations happen from spending an hour in a training hall, but when you go to a weight room it’s to lift heavier weights than last year, not mimic marathons.

So when one can get a good estimation of fiber type in the body, one can start thinking of what can be augmented and what is fighting Mother Nature. One is trying to maximize one’s abilities, not expect a sloth to be a cheetah. The compromise is to be the fastest sloth and hope the other qualities make the athlete competitive. A solution I agree with is to appreciate how one is and design a training program based on getting them better, rather than trying to change them or have them fit your training model. The takeaway is to maximize what one has by having a clearer message to the body, rather than making things too complicated by overthinking. One example is tempo running with very talented sprinters. If they are 80 percent fast twitch jump for joy as you won the lottery, but don’t expect their capillaries to branch out like weeds. Remember you can win the battle and lose the war with fast athletes, meaning you want sprinters to have the capacity for speed, not endurance like biopsies by ruining their mega volumes. So in essence you want to target the endurance or slower fiber types with just enough to get a benefit to show up somewhere else, not get too carried away and turn a promising athlete into a slower athlete.

Running Economy

In the past, speed and endurance seemed like polar opposites, meaning opposing qualities. In truth, they are actually beneficial to each other if done right, but could spell disaster if mixed together poorly. I have focused on running mechanics with every athlete at every speed, including different locomotion strategies. Most endurance coaches are wrongly stereotyped as conditioning experts, but many of the best focus on running mechanics or improving an athlete’s “stride”. As one of my mentors said recently, Running Economy should be replaced by running efficiently, and we don’t mean physiologically. Running mechanics are often thought of as a sprinter need or even a “ running thing “ to team coaches, yet most sports run more than some track athletes. For example, soccer players are on their feet 90 minutes a game and most of them just do dynamic warm-ups and look at film for strategy instead of a fusion between performance and sport technical factors. For soccer to evolve, every athlete needs to run efficiently and transition in and out of play demands (technical motions) and sport requirements (output needs). Everyone should walk, jog, trot, run, accelerate, sprint, and fatigue properly. Steve spent a lot of time and focused on foot strike and other important factors of running with an efficient stride.

Figure 2: Running efficiently starts with good shoes and even better foot function. Running barefoot once in a while helps, but each foot is different, and not everyone runs the same way. We are at the age that we can use powerful software to evaluate the risk profile of athletes and use 3-D printing to customize athletic footwear. If you are not working with a great medical professional, especially a conservative but progressive Podiatrist, you are losing speed every step.

At the time of this writing, RunScribe is releasing their product to help monitor basic foot strike parameters, and that should be part of everyone’s scrimmaging process. The ideal setup for teams should be the connection between the use of Catapult and RunScribe to see how a both volume and distribution of effort interacts with how efficient the athlete is on his or her feet. Anatomical factors are primarily responsible for how elastic one is, but nobody should run ugly and slog through the field like it’s a swamp. Everyone can learn to run better and get better, so each coach has to invest into running better. Being efficient is not just more economical (mileage) but it’s often just faster. Remember all races are about speed. It’s not the person with the highest VO2 max or Lactate Threshold who wins the race; it’s who has the fastest time. Put two twins together with equal physiological profiles and one is a bit leaner and better at running properly, that one wins period. Unfortunately, getting an athlete leaner by helping with nutrition and training loads while juggling running mechanics is hard work and boring. I have helped many soccer players who are not blessed with endurance play stronger from running better, and they are less injured from good running mechanics and not being tired. When an athlete is breathing through their nose and seeing their competition bent over gasping, they appreciate the years of reminders on technique, not just the tempo running volumes in the winter or summer. Endurance is about supporting speed, and endurance is not about volume or distance but being physiologically and biomechanically efficient.

Blood Analysis and Field Testing

Everyone in their 20s or older can tell you where they were on 9/11, and that fateful day was very symbolic to me. That morning our training group was scheduled to go to Sun City Florida, a retirement community that had a great clinic to do a blood test with a few athletes. Instead, we all know what happened that morning, and we canceled our plans and were glued to the TV most of the day. That week the radio was requesting blood donations, and since I am Type O negative, I gave blood often. I am the universal donor, meaning any blood type can receive my blood donation, and this is something I believe to be an easy way to help others. It’s amazing, how such a simple gift can save lives. While it’s not the ultimate sacrifice like donating a kidney or a powerful last gift like a heart, it’s something that most of us can do. The next week we got our blood analyzed, and it was extremely useful because it opened a microscopic world to me and got the root of problems that were hindering training and performance.

Figure 3: Above are a few of the parameters I look at when working with endurance athletes or team sports. Blood analysis is the foundation to my program because when used correctly, the information is crystal clear. I have been using InsideTrackerPro for years, and now any athlete, not just Olympic levels, are getting the same type of support that a professional is receiving.

In the book, Steve Magness reviews how he monitors and performs running tests, and I was very interested to see what he monitored biochemically. On page 56 Steve explained the needed interpretation of Hemoglobin levels (oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells). He points out that hemoglobin without plasma volume is difficult to gage. Steve also shared that hematocrit (percentage or red blood cells in the blood) also may fall from a rise in blood volume. So the question to me was how do most coaches and sport scientists adjust for blood volume in a practical manner? I have calculated hemoglobin mass for years (the amount of total hemoglobin in the system rather than per part in milliliters of blood) but felt that the gas exchange lab testing wasn’t practical and wanted to see how good the algorithm I was using with different athletes in team sports. The solution was clear; each sport had a profile, but Olympic sports and team sports are not the same. Olympic sports like running, cycling, and swimming did most of the training in the environment at which they compete. What was interesting to see was triathlon and skiing, as they had a profile of blood volume based on the weight of the body as well. The lesson learned was that many tests lead to endless tests if one didn’t know the true information for which one was looking. So when I profile an athlete, I look at how the athlete prepares for their sport just as much as what sport they play when looking at hemoglobin levels. One has to do the same with the other dozens of key biomarkers of the body to make real connections. Looking at total testosterone in isolation, even with cortisol ratios requires added information.

The same day I blood testing I do field testing. Why not see how all the dots connect in blood with a taxonomy and currency of scoring with field tests such as speed and fitness tests? Testing doesn’t need to be a treadmill V02 max test; it can be a workout with clear measurement and carryover to sport performance. Everyone reads the research, so why not bring the research in the lab to the field by just testing everything that matters? Here is what some of the variables I look at:

Speed Testing – Maximum Speed and Acceleration with Total and Free Testosterone to Cortisol Ratio is essential here. Warning, a high testosterone level with a young athlete is not an indication of speed or explosiveness (talent), just a status of the strain. A healthy young person can have the same hormonal profile of a drug free national class athlete, so workloads must be factored. Hormones are usually an indication of how precise the training is.

Power Testing – Test lifts and Jumps. Does the athlete maximize their talents or get by on genetics? Many athletes can jump well because they are gifted, but training numbers are great ways to see how they get their results. Athletes need a strength reserve to support their speed as most lifting programs support speed rather than build it. Only weak athletes or neophytes get faster (usually early acceleration) from weight training, and at high levels lifting is usually benefiting training capacity and injury reduction. Add in SHBG and other carriers such as albumin for added refinement in algorithm development. Make sure all your calculations are from quality research since many small journals publish junk studies, and the formulas are often bogus or good for “active kinesiology student volunteers”. I remember doing a study at a university and cringed to see how shoddy the data capture was.

Yo-Yo IR2 test or similar (30-15) – Add Hemoglobin and Hemoglobin Mass scores and screen out folate and ferritin. Other iron scores are needed as well. Many questions can be found when an athlete has speed and power data combined with fitness testing. Is an athlete running well because he or she is maximizing a speed reserve or are they aerobically fit? Remember to use a heart rate monitor and lactate test to see if they are stopping because they can’t continue rather than quitting because they are soft.

Finally, make sure you test the basics as well. While body fat testing, weight, resting HR, and vitamin and mineral status isn’t excited, don’t let easy and simple things derail performance. Even a lipid profile and glucose test can tell how someone is eating and recovering properly.

Adaptation and Personalization of Training

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, or adapt or die like the late and great Tony Wells coined. Developing athletes is not a perfect formula and the success rate and average improvement of athletes in performance ranges from 0-5 percent indicating that no magic bullet exists, just a firestorm of effort in a shooting spree of trial and error. When talking to athletes, I explain that training is submaximal death and a short term poison to the body, meaning heavy training is not something the body is designed to sustain over a day. Rarely are workouts a killer, but that’s what we are trying to do, attack the body and let it adapt. Rehabilitation is very similar to working out, and is submaximal training in a way.

Currently, we are at the age of sport science we know enough biology to have a good indication of adaptation and how the body works. So in essence we know the laws of cooking, but the right recipe needs both a top chef and the best ingredients. As of today it’s likely coaches are looking for the precise dose and proper timing for the right meal because a cold steak and undercooked cake ruin the best ingredients shopping. The goal now is to push athletes safely, and not letting current trends in data to ruin the outcomes of training. Three attitudes exist to records or numbers, those wanting to break them, those that are ignorant, and those that are frightened and see them as barriers. Knowing the sport psychology, we can start individualizing the workouts and the needed personalization of coach to athlete interaction to get the right effect later.

Figure 4: Adaptation is when the body changes. Most assume that adaptation is a good thing, but it’s a process and not a prize. Too much of the wrong thing will show up as unfavorable adaptations, and the results will be less than ideal. A good goal is to see what simple change is needed, and look at the most straightforward way to get there and appreciate minimalism. Confusion is when a workout does everything and genes don’t get the stimulus they need.

Part of the Individualizing Training chapter Steve focused on was testing, something that we already covered, but doing something with the information workout wise is much harder. Steve did a great job outlining this for running athletes, but it’s a great topic to get into more detail. Personalized training in a group or team is much different than when working with an athlete one on one. The constraints of team sports usually limits the individualization, but all sports are constrained. For example, like it or not, the Olympics are every four years, so if you fail to make a team at age 28, four years later isn’t going to be convenient. If a quarterback and receiver need a little chemistry together and one is not available as much because of injuries, sorry, but factors restrict rest and loading parameters. In team practice, usually minutes of healthy starters are the real primary load variable, because everyone must gel together at the same time. If one athlete is a morning person and likes to take two days easy, and one is young and fresh but an evening type, the compromises have to be made for everyone on the team. Many teams’ endurance programs run together and do similar event workouts, but rarely do you see the same event do completely individual workouts by themselves. Sometimes the compromises are needed for practical situations (one coach can’t be in three places) and sometimes the training vibe is so positive it’s worth more than the ideal biological prescription. No program will be able to do everything custom, but it’s a good checklist to create so down the road no stone is left unturned.

Fatigue in the Mind, Body, and Soul

Placebo, Nocebo, and Facebo? It is no secret that the mind is a powerful instrument to getting better. Science for years reminds us that the results of a study are highly influenced by belief, and that is the reason studies use double-blind experiments. Simply eliminating the knowledge of who is getting the variable reduces that chance that psychological factors can skew the data of a study. Bias from a researcher wanting a result can manifest when he or she is aware that the subject (individual being studied) getting the intervention can influence the outcomes. Of course, the subjects themselves are prone to bias when they are informed of the reality of what they are getting. Placebo treatments are basically pretend pills or interventions that create a positive belief so that the real treatment is not getting results because of personal belief. On the other side of the coin are nocebos, or phantom pain from therapists or anyone informing a patient that pain may occur if something happens or do an activity. Pain being part of the nervous system and linked to the brain perceiving a threat, is still not 100% understood in the research regarding the functional purpose of the sensory experience. One argument is that pain is a communication vehicle for self-preservation and gives feedback to the brain. Why is all of this important? Fatigue is highly related to willpower or the volitional motivation of the athlete. An enormous amount of research is pouring in right now on the brain and how the body handles fatigue, and plenty of people are trying to hack the mind for better workouts. If fatigue is less physiologically limited and is more part of what is going on between the ears, can coaches tap into the sports psychology more. The current school of thought is that we can fool the brain by manipulating the mind’s perception, and this is the current rage right now.

Figure 5: HRV (Heart Rate Variability) is a great part of any program and above is the chart I use when an athlete chooses to use iThlete. I am agnostic to HRV companies as the best ones are freely available to consumers and let the athlete decide. Each one has pros and cons beyond price and how the data is calculated, but simple, reliable, and fast is popular with athletes if they do it every day. The chart is like a road map, and the goal is to ensure one is getting the response for which they are training.

This continuum is important, because when athletes give feedback coaches we must understand our responsibility of giving them the right feedback from exchanges and recording objective training. Objective feedback with subjective ratings is important, as it creates a perspective of what the athlete is feeling. The best example of this is likely to be heavy acidosis in training, and showing how an athlete tolerates discomfort. I am trying to use the term “capacity” instead of acidosis or talk about lactic acid because athletes get spooked and become soft as butter when training is hard. If you are expecting pain just light conditioning session can feel worse than it is. Pain science is about emotional and experiences, not just about the anatomy or even brain. Severe discomfort from acidosis is not a problem, but severe pain to tendon becoming damaged is another story. Teaching athletes about “tasting death” and sensing something is wrong is hard one, but this is why a good medical team is useful to help decipher the differences between training pain and possible injury patterns.

Now that the sport psychology and biology is out of the way, let’s talk about application. Most coaches including myself have always seen training as a product of both personalities and sport science, and it’s really not that simple. I do believe that results are what you get your athletes to do, but it’s also about making sure that the science has an ethical element to it. Fatigue and perceived discomfort is a huge trust factor with coach and athletes. Knowing something can hurt and breaking through personal barriers is repeated process that conditions both ways. Some athletes simply burn out from the mental exhaustion of suffering, and some athletes are not properly for battle when competition arrives.

So far in the history of running, no athlete has maintained top velocity for more than a few seconds, even in the sprint events. What is concluded that something happens in the cells and or in the brain of the human body that doesn’t allow for athletes to run all out forever, so most run at a submaximal speed based on their speed talents (maximal speed) and their fitness (current endurance levels. What track coaches are trying to do is either maximize speed absolutely (sprint coaches) or work on conserving and extending speed (middle and long distance coaches). Team sport performance coaches care about conditioning that allows for the best composite of speed and endurance and want to work on both to a point. Overall, every event from 100m dash to team sports to the Marathon care about the balance of speed and endurance that gives the athlete the best winning combination. None of the aforementioned information is new or earth-shattering, but when workouts are prescribed it seems that the big picture is lost with a limbo style of training. Limbo is some sort of workout that has no clue or purposeful approach, just throwing in a lot of stuff that fatigue athletes, but never sends a clear target to the genes to improve.

For simplicity, we must always juggle the idea that speed is always the prime factor in endurance since the fastest guy always wins. Endurance is about training that supports speed, not being the mirror opposite of speed and just a result of volume or heart rate zones. One way to prepare for events or sport is to compete more to get the specific adaptations to imposed demands (SAID principle of training) or simulate the demands in different degrees of volume and intensity.

One of the changes when one moves beyond the 200m is the need of careful pacing strategies based on one’s abilities. This is a tricky subject because fatigue and current fitness are hard to juggle along with mental toughness. An athlete may not be aggressive, but can run faster, making coaches more a motivator and sport psychologist than a trainer. Steve Magness points out that sometimes a point in training athletes need to move from feedback and just move. So how does this work in events like the 400m hurdles and up to the marathon? What about team sports?

The cornerstone to blind feedback is to focus on internal elements such as finding a rhythm and establishing some mental toughness. I use this during taper conditioning as a guide, but still time to see how athletes perceive speed and workout prescriptions. Sometimes athletes surprise me, but sometimes it’s like clockwork and they do the same thing as they normally do, so blind timing with no quantified feedback is helpful to see how athletes respond to coaching support. Many athletes autoregulate their workouts, meaning they adjust their efforts and output based on how they feel, not just on their prescribed session or the output of their training. Taking advantage of subjective readiness is not easy, since many athletes are more talented than their work ethic, thus creating a problem of leaving the output of training to the athlete. Group training is also challenging since some athletes will give effort on different times they feel good, and some athletes are slaves to pain and equate harder being better. Coaching is not just writing good sessions and collecting data; it’s more getting the most out of different personalities in different cultures and environments. The takeaway here is that Blind Feedback is not something you can just “Try on Monday’s workout” and requires some planning and careful attention to detail. The application of Blind Feedback is simply allowing the athlete to run at the pace they feel either comfortable with and keep things very open or remove the mental barriers and let athletes push things. Both ways, going on one’s rhythm and pushing one’s mental limits is about knowing when to let the athletes remove the sterile and calculated world and let things become more spiritual and emotional.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

I have never read, but I am going to have to check it out. Thanks for sharing.

Great write up. Will now be buying the book. Carl, Human Locomotion has been very detailed and informative on the mechanical side of things. Michaud seems to be obsessed with biomechanics.