By Carl Valle

When they hear the word “conditioning,” some coaches and athletes believe that power development and speed training are the priority, with conditioning tossed in as an afterthought. To me, though, conditioning offers a continuum of benefits—ranging from active recovery to the most brutal lactate speed endurance work in history—rather than an opposing quality.

For ten years I have worked privately with athletes in different sports, ranging from bobsleigh to soccer. Having no emotional attachment to training methods, I look at what it takes to win, not what is fun to coach. Let’s be honest—it’s usually far more exciting to be in the weight room working on explosive lifting or on the track teaching speed. But if conditioning is left to chance, all the hard power work crumbles like a house of cards. In this article I will share six staples I have used and fine-tuned over the years.

Aquatic Regeneration

Pool workouts are still the most underrated option and therapeutic modality, bar none. It’s widely known that they are great for unloading joints because of the eccentric deloading, but the hydrostatic pressure is like adding half a day a week of recovery. That adds up, and by the end of the season those who are dedicated and committed achieve noticeable improvements in the autonomic and hormonal systems. Coaches have to find a way to organize and administer the burdens of finding a pool and getting the job done.

Figure 1: Pool workouts can be monitored with aquatic specific heart rate monitoring tools such as the Cardio Swim system from Freelap. I will write more about how swimming, team sport recovery, and triathletes can integrate the split and velocity tools of the system later.

The realities of contact sports like the modern NFL or elite rugby are obvious. The body takes a beating over time. I like doing pool workouts the day after a game, though for some reason some teams lift heavy and hard then. Coaches want to get a good workout when the athletes are willing, with the pain drugs and adrenaline still creating a window to train. I can’t speak to the medical side too much, but athletes need ways to recover and train properly. Back-to-back hard days are often thought as foolish, but what does one think happens when they “get the lift done” with back-to-back intense sessions?

I have identified four stages of hydrotherapy, based on how broken-down an athlete is.

Dead: Those in so much pain that they can only hit a whirlpool and play with thermotherapy spa interventions. This creates a rebound effect, according to research by Dr. Buchheit and colleagues. I have had an intern or two swing by and force exhausted athletes into a few hours of therapy-like options. By the next day the measured changes are real with HRV and other indices of recovery.

Crippled: Athletes who complain of pain and soreness of both joints and muscles do simple restoration workouts that mimic tai chi and aquatic yoga routines. The goal of the sessions is to get moving and focus on creating an active range of motion.

Banged Up: Athletes who are simply sore in both joints and muscles and a bit broken down from heavy training but still have some energy need to do more than recovery workouts. They need to be pushed with a session ranging from 40-60 minutes. Goals include a heavy focus on challenging the heart and lungs with deep water interval-style routines and leaving tired but feeling better than when they started.

Sore: When athletes are only sore with muscular discomfort, I don’t want treat them like little kittens. Sometimes deepening recovery with a demanding pool session can get some of the benefits of fitness without risking injury. Soreness is normal and part of the process, and pool workouts that are shallower and more explosive in nature are effective. Adding squat jumps and other patterns improves performance with added benefits from the water resistance. To functionally overreach athletes, have them invest a full hour weekly during the year.

Bike Work—From Flush Ride to Chain Massacre

Bike routines are overused, bastardized, and often unfairly eliminated from training. My belief is that they should be placed into two categories: alternative secondary training for speed athletes, and complementary training for team sports. Bike routines can add a little extra to a comprehensive program and teams have won world cups using them, so people need to calm down with fearmongering. True, any activity has pros and cons and even bike workouts have risk. Ironically, many pundits who suggest that bike workouts are evil are the same ones complaining about unfit young athletes because Mom and Dad drive them around instead of the child biking.

Figure 2: Something as simple as three bike workouts a week can make structural and chemical changes in the body, and the “cost of doing business” with not as bad as people think if the workouts are not too aggressive. Many fear hip flexor tightness but a complete program should offset possible restrictions.

The truth is that nothing is perfect, and bike routines are appropriate when an acute problem exists. As a track coach I prefer running whenever possible, but what happens when that option is not there? The spine is important and I realize some experts and gurus warn that flexed positions will create problems biomechanically, but how great is that risk? Some claim huge problems with muscle imbalances, and yes, a problem with any sport or activity is an adaptation not favorable to other activities. So what is the verdict? Be aware of potential issues but don’t eliminate options.

With proper bike fitting and a sensible expectation of bike routines, risk is very minimal. But an issue now is that many see bike routines as the Holy Grail or overdose on them. A flush ride a few times a week isn’t going to ruin a career, and if an athlete can’t do an easy spin workout they are basically frail. Bike work works, period. Most research we see on adaptations physiologically involves bike sessions because they are easy to measure and control, so those benefits are valuable to teams dealing with foot fractures and other problems. Muscular and spinal issues are researched in depth, and injury patterns can be mitigated by making sure that mechanics, load, and preparation are done with the athletes using bike sessions just like any other part of training and not worry. Overzealous use of bike work besides easy fitness routines can be a problem, so moderation needs to be promoted.

Here are two workouts.

Easy Spin: 30-40 minutes a few times a week is not a big risk as part of a comprehensive program. A common fear is tight hip flexors, but not using them isn’t going to keep them long and strong. I like a steady heart rate and teaching the body to get into a continuous rhythm. I find that low-intensity workouts focused on a percentage near the lowest threshold show up in general aerobic fitness tests if done twice a week for two months, but they need to be maintained year-round. Transfer onto the field is unknown as I can’t create a control group that doesn’t use something I believe in.

Hard Intervals: Athletes who can’t run for extended periods because of medical restrictions eventually need enzyme induction work or they find the transition to the playing field or track sluggish. Adding modifiers to routines such as RPMs and resistance is subject to debate. But after 10 years, I think the truth is that most adaptations get cancelled out when the entire program is factored in. The best solution is to keep it very binary: high RPMs in 30-second bursts, and easy 90-120 second recoveries. Other work-to-rest ratios are very effective but keep in mind that the goal is to get positive adaptations without too many variables hitching a ride and creating baggage. Twenty minutes of intervals, not including warming up and warming down, is enough to make a positive change with national-level athletes.

Reboot Circuits

In 1998, I was getting my USATF Level II Sprints and Hurdles certification with the buzz about LSU jumps and multi-event coach Boo Schexnayder permeating in the hallways. During that time, a discussion occurred about the use of General Strength Circuits, and I was a little skeptical about how submaximal training worked. Leaving Florida, specifically the grass and sun, years later made me value how a light circuit can act as a placeholder and stoke the fires of fitness. Elite athletes need variations that don’t hinder specific intensive work.

The primary problem with circuit training is that athletes never adapt to the circuit or general preparation earlier and struggle to use them during other periods of the year. A low-level circuit must match the abilities of the athletes. One elite athlete switched coaches from high school to college during her freshman year and simply dug herself into a hole. With no formal weight training, just doing lunges and bodyweight exercises was strength training for her. Because she was never recovering, she ran miserably until an assistant coach pruned the workload. Even explosive and well-developed athletes must be careful with circuits. After a hard session the athlete is torn-up and tired. Circuits are truly stimulatory and must be more light-fitness options.

Figure 3: Monitoring options like using InsideTracker, ithlete, and even consumer level products that track fatigue are valuable when looking at the weekly setups. No research study will research your program, so you be the sport scientist and figure out what is working objectively.

Circuit training can range from tightly planned and highly organized sessions involving national team sessions during peak periods, to an embarrassing blender of random exercises. Since many people believe that circuits improve work capacity, they seem to have poor expectations and principles because they are not expected to do much besides getting people tired. Circuit training should represent a tiny fraction of training, yet we are seeing the contribution of circuits now more than ever.

The result is athletes who are not being exposed to intensive options and get hurt more and more. Those doing intensive training are finding some poorly designed circuits overtraining them, as circuits are the ”Wild West” of training. With very little enforcement, circuits seem to attract a lot of “outlaws” or gurus who throw in a hodgepodge of battling ropes, random construction and labor equipment, and physical education exercises. I don’t have a hateful bone in my body, but removing circuits from training altogether wouldn’t make me lose any sleep.

To be fair, I have benefited from a circuit as an athlete, and still use small and long circuit options. Instead of randomly tossed exercises or traditional intervals and repetitions, I use circuits to organize time, bodies, space, equipment, and the biology of athletes. I find the common three trips around 8-12 stations with general core and basic exercises as a good starting point. I like focusing on core training since intense days seem to be very little juice for the weight room, and I don’t want people to feel like the walls are prison-like. I use ancillary upper body and core exercise selections as time-efficient ways to get in secondary work, and the investment isn’t overly demanding.

The benefits are real, and many athletes find the wellness routines to show up with elevated moods and willingness to train subjective scores. This can be for several reasons. Research on circuit training combined with speed and power programs is not available, but I have seen several valuable changes with brain chemistry showing up in EEG and opiate responses. I was very skeptical of what a pump can do as it has no ergogenic values, but feeling good and having a visually complete body must have some mental benefits.

Circuits sometimes become sloppy if they are high-rep and based on getting a lot done quickly. So a good idea is to think about contraction times of 40-45 seconds and using the transition walk to the next station as the rest period. I use circuits for core and support exercises and sometimes we do bodyweight upper body exercises or light strength work, but I have not done lower body training for years unless it’s in the early GPP. Doing reps near the 6-8 range with control is key, and if you are doing a left and right combination such as Pallof Presses you can switch quickly halfway through the station or switch directions and sides on the next trip. To me, circuits are just a way of organizing better training and cutting time without cutting results.

Classic Tempo Running

Tempo running, while simple and timeless, often is not valued and implemented properly. Let’s be honest—conditioning runs are less-than-exciting and repetitive, to say the least. Nobody is more guilty of this attitude than I am, but I have invested into interns who were hungry and given them plenty of opportunities to implement a classic tempo program with team sport and sprint athletes. I shared some general advice in my article about mistakes with tempo running, and reading it is a great start. So here are some very basic routines. I have divided the running options into three general groups:

- Lengths – Straight running for a certain time or distance with a given velocity

- Laps – Curved runs that start and finish at the same location with a consistent velocity

- Légers – Straight runs that require a complete change in direction and reacceleration

Running conditioning is still demanding on the legs regardless of the speed. Footstrikes generate impact forces, regardless of surfaces. Different locomotor strategies will create different strains on the body, down to the specific metatarsal. Running impact is cumulative so a copy-and-paste job of running for an entire month is lazy and will likely result in lower limb overuse syndromes.

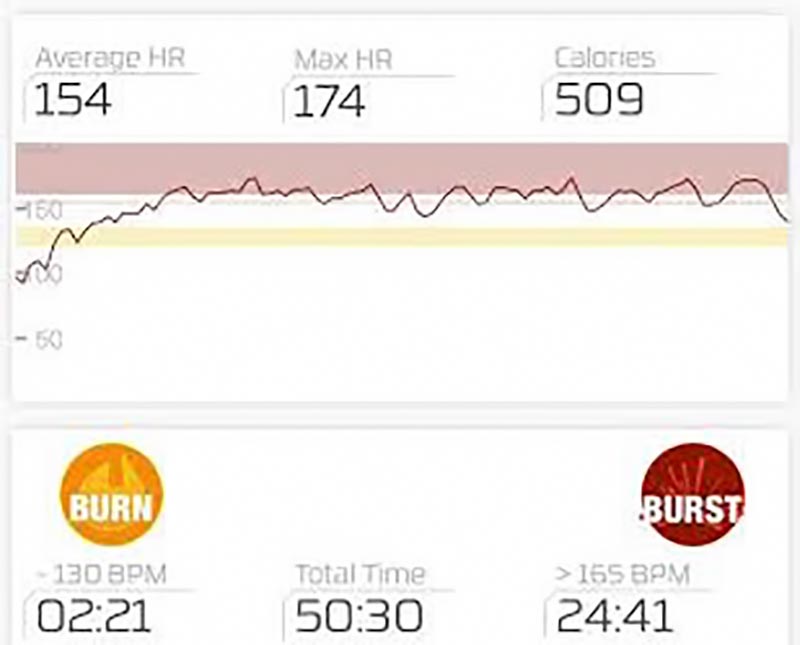

Figure 4: Heart rate data is a very simple way to see how an athlete is improving or possibly getting overtrained. Look for rapid “free falls” between runs, and lowered heart rate scores during speeds that are normal. It doesn’t take a team of PHD experts to see if an athlete is changing with a simple line plot.

The solution is being there and listening to athletes without making them think they are medical students or wounded Civil War soldiers. Good tempo workouts are just enough to improve things, but not to the point where they ruin the goals of the speed and power sessions. I look at pure speed athletes doing 2 Kilometers of running 1-2 times a week, team sport athletes who need light conditioning running 4-6 Kilometers 2-3 times a week, to heavy endurance needs of 6 kilometers + done 3 times with supplements of practice or prescriptive cross-training. Remember the higher the volume and the greater the speed, the more likely that overtraining will occur. I would rather go slower and do more continuous running in the lowest aerobic zone rather than reducing rest and shuttle work, as the cutting is too much. Here are my three favorite options.

Monday Morning Quarterback: Nearly every NFL athlete has run lengths of the field and walked the widths as recovery. Sometimes the volume is so low that no possible aerobic benefit is there, but if done right it can screen for fitness changes over the course of a season. Usually, the work-to-rest ratio is something like 1:2 and the intensity or speed is about 50-70% of ability.

Giant Curve Runs: My bread and butter is teaching nonsprinters to stride 200m by running a large U on a practice field so they can learn to run properly. While cues and great coaching are the cornerstones, athletes need to run in practice if they are to run in games. Everyone now seems to be afraid of running, but I have yet to see a running-free program dominate any sport. I focus on instilling the idea that good running feels better and is easier, and I am careful not to focus on speed. “Maximum Beauty” ,as fast as you can maintain good technique, a very safe parameter, and when running mechanics drop, I stop and move on. Going three sets of 5x200m with 30-40 seconds rest between reps and 3 minutes between sets is my most common prescription. I like alternating directions by set, so athletes get exposed to clockwise and counterclockwise patterns. Mixing footwear, curve radius, speeds, and even acceleration rates all help keep athletes sharp and not completely bored. Surprisingly, some athletes like the break from coaches barking at them and enjoy the solitude or peace of just plain running.

Beep Test Rehearsal Work: Running back and forth with either set intervals or stage testing like the Yo-Yo IR1 and IR2 tests are workouts. Other fitness tests like the 30-15 and even customized tests are fine workouts while exposing the athletes to tests to remove familiarization and pacing with testing. Athletes will get better at tests without getting better physiologically, so I like getting the false improvement issues out of the way by using some tests or rehearsal type activities early. Doing so well gets better validity earlier in the first few conditioning tests, and removes administrative and testing issues down the road.

The Springbok Project

Dan Baker did an amazing job with his work on improving Maximum Aerobic Speed (MAS). As a result, pace work in soccer and other team sports is starting to get more detailed. I want it all: freaks or aliens, not athletes who are simply passing tests or doing the minimums to play. Those who are afraid of overtraining or getting athletes injured are usually making excuses why their athletes aren’t faster, fitter, or freakier in size and strength. In their defense, many strength coaches make me rethink safety and overtraining by looking at the research and asking around to see if what I am doing is outdated.

Coaches need to embrace evolution and respect history at the same time. Each year gets better, but major changes are unlikely when it comes to training. Conditioning is not much different than it was years ago, so if someone claims to have unlocked some magical workout you should be aware that it’s usually too good to be true.

Baker’s article talked about body speed in the fitness tests. So I asked, what’s the limit? How fast and fit can a soccer player be now? Asking around, I found that maximum aerobic speed is 5.2 meters per second. Wanting more information, I asked a few coaches I trusted for the best performances they witnessed and 5.2 was indeed the best time for a soccer player. Having a thirst for what most coaches want, I needed to break 2,000 meters in a 6-minute running test while still having a skilled and fast athlete.

Figure 5: Advanced metrics like Pace, Speed, as well as simple HR indices can help get more out of the workout. Since teams are pressed for time, every session must be as close to prefect to get the desired effect.

The last thing anyone wants to do is produce a slow cross-country athlete with no touch on the ball, so I looked at the research some more and found the reason it’s so hard to improve MAS: lack of training time. While practices do give some training effect, ball work in soccer or skill/play work in rugby and American football make it hard to improve physiology when team coaches are in charge. I have said many times that when a performance coach who is a brilliant strategist and tactician becomes a head coach, it will be a turning point and evolve the game.

Performance coaches are better monitors and more vigilant about overtraining when doing 3-minute runs with active recovery periods. Getting 6 or more kilometers in workouts in addition to practices can trash athletes if they are poor runners and are weak and flat (poor elasticity). The approach to the runs is fairly simple: adjust the speed and distance but not the duration of the run or the rest period.

The jog velocity (with the ball or without) can be static, but the athlete is expected to cover more ground and do more in no particular order. Depending on the program, some coaches find that they want to do six rounds of paced aerobic work, while others like doing 4 with a focus on quality. Shorter runs and absolute rest work nearly as well, but if you want to squeeze more out of an athlete you will need to go longer and faster with less rest.

Testing for MAS using Baker’s suggested methods, I find that going shorter and faster (3 minutes compared to 5-7 minutes) with passive rest up to 2 minutes is great, but pacing at 100% with incomplete rest and half the distance overloads really well. I also find that conditioning adaptations decay slower, but that is just an observation of a small subject pool. Here is my progression of MAS training for light athletes (soccer, lacrosse, and some rugby players):

- Stage 1: Complete the workout (finish six rounds)

- Stage 2: Become consistent and stable (last one as fast as the first)

- Stage 3: Progress to hit benchmarks (improve weekly or every other week)

- Stage 4: Break barriers (ramp up by manipulating variables)

It’s not complicated, but I expect people to finish the distance first as it’s an open pace. If you can’t finish a run 6 x 3 minutes at a slow clip, you are out of shape. After you can complete the session, the next goal is even speed and even effort (via heart rate). After being consistent, get farther and faster and watch the impact on HRV and HR for fatigue and residual soreness. After you hit 800, playing with variables such as speed and volume (doing 4 fast instead of 6 even) may help break plateaus.

Nuclear Meltdown

The most controversial topic I have written about is sprints from 150 meters to 250 meters with track and field athletes. The reason is the difficulty of knowing how many sprint world records reported in the 1980s and 1990s are factual. Many coaches want to know human limits in performance and drug-free options for improvement.

The Infamous Workouts – Without naming names and coaches, I have heard some amazing stories of workouts by world-class athletes. Before a major championship, the last few preparation weeks have had a window of time that magic can be brewing and some sprinters (200-400m) apparently have done some “wicked” sessions. I have witnessed some amazing workouts. Some warm-ups have been legendary, such as Mo Greene’s warm-up in Atlanta during indoor nationals. Looking at the most demanding output I have collected, it seems that speed endurance sessions with short rest are producing some serious biochemistry.

Nobody has the perfect answer to the mystery of acidosis, and some people are sharing a lot of bad science. Some think lactate is a sign of fatigue, some of hard training, and a few think it’s the adaptation marker of choice. To me, it’s simple: faster results from faster workouts. Too fast and overtraining may occur, not fast enough and the athlete doesn’t adapt. Eventually, one has to get faster from something, and that is better races (competition and conditions) and better training.

Figure 6: Some debate exists if running tempo is going to create weaklings or dead legs and the truth is a run at 80% may elicit some positive hormonal changes. I have seen basal (resting not acute) increases of IGF-1 with athletes increase significantly when eccentric loads and speed endurance is added. Acidosis is interesting and people love lactate testing, but focus on getting faster and let the physiology explain the improvements on the clock. I don’t care about anabolism or catabolism debates, I just like faster times from better training recipes.

The primary takeaway from acidosis is that the body needs to be fast enough to fatigue at speeds that matter. Some aerobic training will help with capacity, but if you want an alien you need to release the devil and burn down the athlete. Athletes with amazing fitness levels will sometimes reach up to 20 mmols of lactate, and workouts that produce pH drops will eventually teach the body to enjoy the pain. The most common error is reducing rest to increase acidosis. This makes athletes great at repeating slower and lesser outputs over time, instead of getting absolute outputs first and learning how to repeat them. Any coach can get someone tired, but getting better usually means more speed and distance (length and/or volume) first.

Athletes constantly in glycolytic activities seldom get better at advanced levels, and polarized training is growing in popularity for good reason. While it’s great to cover the bases, sometimes changes occur without velocity, and sprinters in the 200-400 can do some quality work and expose themselves to serious pain. I used this workout outline only a few times, but it was a baptism of acidic fire that seemed to change athletes and their mindset to real training. All you are looking for is progress, not a magic number. I don’t know if this works better than other options, but I know it has helped a few athletes in the past.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]