By Carl Valle

I ran a 40 at the Combine and I haven’t run a 40 since. It’s not a great representation of what offensive linemen need to do. A five-yard burst, a 10-yard burst, lateral quickness. That’s what we do. — Geoff Schwartz, NFL Lineman

Every winter for one month, the combines for the National Football League and Major League Soccer draw a huge amount of attention in the media for what is simply a day of performance testing. Yet, after the combines players seem never to get tested again making me wonder if the numbers are so valuable shouldn’t teams test again to see if they are getting better, staying the same, or getting worse. This article will review two points that everyone should know: that testing is important, and you must be able to understand the relationships and limits of jumping and sprinting.

Why the Combine is Vital to Player Development

Some criticisms of the NFL and MLS combine have used poor arguments against testing players speed and power, and they are worth bringing up. The myth that the combine is useless when Tom Brady is shown on video or the fact that Jerry Rice ran a 4.6 is always brought up. True, the fastest guys are not always the best players, but if the players are performing at a specific speed shouldn’t we at least maintain their abilities? What is so strange is that the same people that value speed when selecting players seem to forget retesting or even development. Is the guy great in spite of his speed but can get better? Is the athlete untapped athletically because they compete year round? What are the cause and effect of the weight room and other influences to performance if one isn’t testing at least year to year? Testing every month at least shows some trend, but most stop testing after the player reaches a high level. For both the NFL and elite soccer to keep the best players healthy and develop more athletes, it’s a good idea to test from youth to retirement, provided a wise perspective is included. Retesting speed is the most effective way to gauge what is happening to a player besides fitness testing. However, few teams are doing it because they are scared of injuries or don’t have confidence in the training program.

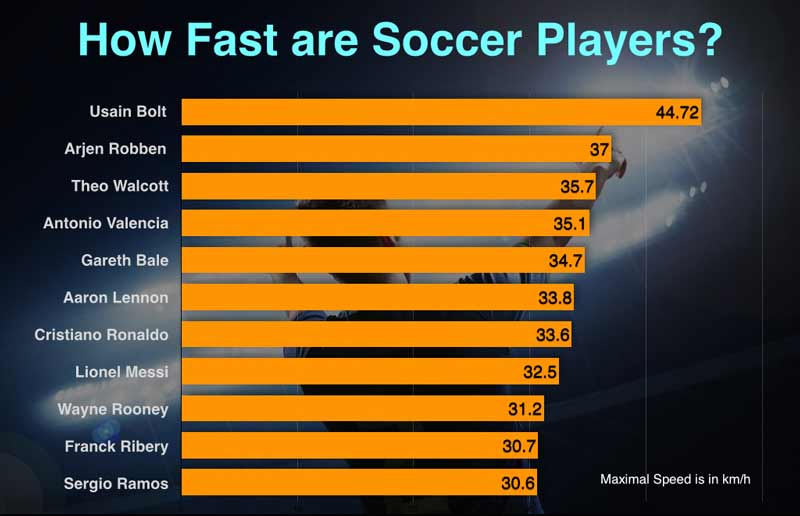

How fast are Elite Soccer Players?

The NFL and Elite Soccer look at speed differently, and science and media report how fast athletes are based on different measurements. Speed is a very general measurement, and the distance an athlete is running determines how fast one can be, and how they are getting there. In the early article on Usain Bolt, the question many search on the internet is how fast the Jamaican can run the 40 yard dash, a test of acceleration. In the United States, the 40 yard dash being such an important indication to many, most Americans don’t know what the maximal speed an athlete reaches in sport. Basketball, baseball, American football, and hockey don’t have a long history of showing top speed in plays, and if they do they show times from past combines or how little time was taken to perform a play. For example look at the Super Bowl, the replay of the offensive attack of Tom Brady was shown as snap to pass in a chronometer in the top left of the screen. Since most sport is acceleration, very few times we can see plays that are long enough distance and time to hit maximal velocity. Regardless, elite soccer does capture maximal speed of plays, and you can see how they compare to the World’s Fastest Man, Usain Bolt.

Figure 1: Maximum speed of elite soccer athletes.

As you can see in the chart above, the speed of the players (taken from ESPN) is impressive, and for convenience we provided a table to help coaches understand splits and speed. When athletes are being tracked on video or with GPS tools, the data is estimating how fast they are running, but timing systems like the Freelap Pro Coach are the gold standard. Since most athletes hit top speed from the 30-40 sprint, and elite sprinters hit top speed typically between 50-60 meters and decelerate slowly after. New research is starting to emerge, and players are tested longer than 30m to get both acceleration and top speed conveniently.

How Fast can MLS players Accelerate?

Figure 2: Acceleration of elite soccer athletes.

I love the fact the MLS Combine tested the 30m sprint. The reason is that meters are universal. They measure the first 10m, showing they understand the value of early acceleration, the period from 0-5 or 0-10 meters. Based on the combine data one would ask the obvious question, are the times accurate? The answer is complicated. Like the NFL combine, each approach is unique in protocol and equipment. Having electronic timing (not hand-timed with a stopwatch) is a good start, but different equipment usually means different protocols of how an athlete is timed. First step, first movement, or the first sign of displacement? Different equipment will mean different times, so it’s hard to tell when combines report times. It doesn’t matter, since we know from research on the world’s best athletes in soccer none are outperforming the NFL athletes, but different sports are apples to oranges. The takeaway of the chart is that the majority of soccer players are unlikely breaking 4 seconds in the 30m dash, and most of them are not running much faster than 30 km/h at top speed.

Analyzing the MLS 30m and Vertical Jump

The most straightforward test in sport is a linear speed test. How fast are you from Point A to Point B? One problem with something as simple as a 30m sprint is that other factors can affect why some run faster times but are not faster athletes. A player standing or crouched makes a difference, and how a player is timed is an obvious factor. The 2015 MLS Combine was a very interesting testing event because of the equipment used. Remember that the MLS is a young league and is slowly creating an identity internationally and with their sport science. The MLS is starting to stabilize their testing, meaning they realize what information is important when drafting players out of college. Many college athletes are not use to being tested in meters since most colleges in the US place emphasis financially on American Football and some still test in yards. The 30m test is a great way to assess acceleration abilities, and if one stretches out the sprint to 40m, one can get a flying 10m sprint for maximum speed. How fast someone sprints and how they sprint is the ultimate evaluation tool for potential of injuries and how deadly they are in games that include longer plays. The highest probability of success in professional soccer are fast running plays, and those that are fast and can keep their speed with fitness are the ones wanted. Nobody wants to see a montage on conditioning tests; scouts and agents want fast players.

Figure 3: Vertical Jump.

The vertical jump testing was another surprising test option, likely done because athletes are not use to sport science analysis. When we use the term vertical jump, most young athletes will think about reaching up and touching something as high as possible. When specialization begins to pollute youth sports, athletes loose athletic capacity and being to become better players, not better athletes. Why do I bring this up? American athletes will always be developing great goalies because they are used to catching and reaching above their heads, but in soccer one can only touch the ball with one’s head if you are playing a different position. Most jumping plays that score are from corner kicks where the ball is purposely played to allow for heading, thus making most of the jumping ability a stepping up jump over a static one. Arms are used, but not to the effect of a traditional vertical. The ability to jump is important in sport because so many situations the ability to make plays in the air is essential, but the cardinal mistake is that jumping high means a direct correlation to running fast.

As you can see, the fastest athlete and the best jumper are not the same. Look at the data of the fastest NFL players and their jumping ability you will see the same conclusion. Just because you run fast doesn’t mean you are the best jumper, and the opposite is true as well. Just because an athlete jumps high doesn’t mean they are going to run faster than those who jumped lower. When looking at the top athletes a small trend exists, all the athletes are well rounded, but very few excel at jumping and sprinting. So what is the position here? The position of the value of the tests is that getting faster means one must focus on running faster, not resorting to lifting weights in hopes that you will jump high and far and run faster. The biggest leap of faith, pun intended, is that lifting weights will automatically make you run faster, and jump testing can predict how fast one is going to sprint. For years everyone has chased maximal strength or power and have seen inconsistent results for a reason, beginners get better from exposure, and elites are fast mainly because time and genetics let the cream rise.

Using Applied Sport Science to Support Speed

I like combine data because it’s a starting point for development discussions and the baseline to long term career sustainability. Combine data alone doesn’t do everything, and a good idea is to see what is needed to preserve speed and power. A lot of the game can sustain an athlete, but at some point more than practicing and competing is needed to get better or maintain. All of the recommendations below are not earth shattering, but if you put your energy into them athletes will be as fast or faster later.

Test Every Year – Testing speed is not a sin. A lot of coaches are scared of speed testing, and two common fears are injury and being exposed. Timing to me is the most humbling because it is so pure. At times it breaks your heart, but you have to test if you care about keeping athletes performing. If you are afraid to sprint all out, you don’t have confidence in your injury reduction program or your program, in general. What you are doing by not testing is playing roulette and playing hot potato. Hot potato is simply getting the problem moved to someone else instead of taking accountability. Speaking of accountability, if you are afraid to time, video analysis and sensor technology is evaluating games, and that means evaluating speed of athletes. Timing now before it becomes mainstream is a wise decision.

I test standing, crouched, and three-point in order to see if my athletes are getting speed that transfers. Most athletes that do well in three-point starts are skilled and trained, and I have found that athletes who are strong and fast simply do better in repeat sprinting because they don’t deplete themselves from not having a strength reserve. I have done 40 RSA (repeat sprint workouts) tests in eight years and those that have a better capacity than those that rely on good fitness. It’s not an either-or, it’s about a balance to include both strength-to-bodyweight and being honest about general aerobic work.

Quantify Lifting and Speed Training Monthly – The reason Velocity Based Training is popular is because one can quantify the metrics that matter beyond weight. Obviously body weight to power ratios matter, but other metrics like eccentric parameters and RFD, the ability to create force rapidly, all help see why speed increases or decreases when running. Several companies that make sensors or tools for the weight room are chasing bar velocity in average and peak form and that is OK, but below the surface is what coaches want and need. Lifting weights are for growth in muscle mass and ability to get the lifts to transfer in reducing injuries and making players more efficient and faster on the field. Transfer, not bar speed or just power indices from the 1990s is the name of the game. I have used every device on the market and believe that lifting is about supporting speed and repeat sprinting, not about getting guys faster unless an athlete has poor strength levels. When an athlete hits their genetic ceiling lifting is more about injury reduction and less about speed development. Lifting at advanced levels become more than just getting guys fast, it’s about getting guys to be fast year round.

Perform Jump Testing Weekly – Jump testing correlates to speed slightly, but if one compares athlete scores to themselves, don’t worry about research that fails to take account of all the variables. The ability to jump far doesn’t mean one will run fast, but if an athlete runs fast with good jumping and their jumps decrease and speed follows, make sure you monitor jumps as it’s easier in team sports than testing speed. Great news though now that the new Pro Coach is now available. With the Pro Coach teams can test jumps and sprints weekly by doing warm-ups that include submaximal sprints. Smooth sprints are in my opinion the most underrated diagnostic tool. It allows athletes to autoregulate their efforts, measures their short sprints, and protects them by encouraging relaxed repetitions. Just doing a few bursts, even just six in the middle of the training week, keeps athletes sharper than not sprinting at all. Jump testing connects the dots in power and fatigue and can embed into warm-ups before the main lifts like cleans and squats. Add in flat screen TVs and music, workouts add a little feedback and energy instead of going through the motions. Athlete UX or user experience is more important that looking for perfect periodization. Fight for results and make science fun.

Watch Body Composition Changes – The simple need of being lean and preserving muscle mass is obvious, but because it’s not exciting and requires discipline people are not engaged. I have my athletes weigh themselves every day and do DEXA scans when they can. Weight is the easiest metric yet it’s a little boring. The solution is easy, making the boring fun and spice it up. Next to a plunger, the most common bathroom item is likely to be a scale; make sure athletes have access to a WiFi scale as 90% of pro athletes are not 300 pound monsters with size 18 shoes. NBA and some NFL athletes require more, but NHL, pro soccer, MLB and other athletes just need to weigh themselves daily. It sets the tone and gives meaning to why some are slowing down and why some are being driven to the ground. The pattern I see with athletes is that many who are a little out of shape (not lean) before the season starts become too light from not being durable at the start. Athletes who are trying to shed fat end up losing muscle too quickly later, and the opposite problem beings to slow them down. Athletes that lose muscle will in all probability lose power unless it’s a slow and steady progress. Most coaches know this, but the margin for error hormonally is greater than we think. This is why the relationship between hormones and body composition is not a simple as being lean equates to anabolic, since many athletes who get lean the wrong way will impair their recovery ability down the road.

Range of Motion Tests are Still Valuable – Many fast athletes are not flexible, but changes in flexibility to me means the tissues are overloaded. I have seen countless measurements of tissue diagnostics ranging from Myoton scores, TMG analysis, and elastography that those that toss out flexibility are those that don’t work with athletes in speed and power. On the other hand, many therapists think they are making changes in tissue. The truth of the matter is soft tissue therapy is expensive, very slow to make changes and simply isn’t a good investment for the layperson. For an athlete, it’s everything. Each person has norms that matter for them. I like reverse screening, meaning getting data on athletes when they PR (Personal Record) and seeing the tone (activity of tissue) and the range (extensibility) of each athlete before the race. Why try to be a smarty pants with prediction when one can be a genius with confirmation data? What you will see is crystal clear, great supple and even tone rules. Range of motion only matters when it is reduced significantly. Range of motion still matters because training drives performance and squatting at 100 degrees will not help those trying to get glutes and hamstrings better. So to develop athletes, think about what you need them to do to get better. The need for sane understanding of the range of motion testing is a difficult one, but having below average flexibility has never shown to be ergogenic. Having a reserve gives one a better chance of success provided one is strong than being restricted.

Getting Started with Testing and Long Term Development

The first step is easy, test and see what the supporting data tells you. Coaches, including me rationalize poor times and get too excited about testing all the time. A conservative and patient approach is to test frequently and see all of the contextual information behind why athletes get faster and slower. Jumping power is important, but the data shows one can be fast and not blessed with the equal ability to produce force in a vertical jump. In closing, the shrewdest approach to long-term development is test and training consistently and let the recipe emerge from the mix of ingredients and measurements.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

Y’all don’t know anything about association football!

There are definitely lots of smart people who know about athletics in North-America/the-USA. It’s very important to have people in charge (managers, scouts, …) who are smart & know enough about the sport but even at the very top level -where they pay a lot more- they can still be stupid at times (also nobody can know everything, if they claim that they do then they are probably stupid &/or full of shit). When the person in charge doesn’t know enough about tactics it’s very easy to just chase a ball up & down a pitch (especially when the sports science knowledge has become very good). The teams in Europe which were able to play defense properly didn’t have fast players when they won the World Cup (maybe a few but definitely not for the most successful ones ie: Germany & Italy, Germany might a fast player next World Cup). The teams in South America who were able to play defense properly definitely did have fast players. The deep lying playmaker is more European than South American. Proper defense is definitely required to win a World Cup. Possession football is optional. Nobody ever made it past the quarter finals by going up & down the pitch a lot (probably way too much of instant gratification & not enough intelligence). Against a proper defense you will definitely need to play with only a few touches on the ball (usually 1 or 2 touch football), preferably with shorter passes (if the defense falls asleep then it’s a long pass not hit & hope) ie: definitely be realistic if it’s not a youth team.

The trend can always change but changes will need to be made in what the people in charge think is the right direction. If you are athletic & can think quick then you will have to choose your sport & youth system. Look at who you can realistically try to be like & try to join the youth system that produced them (shouldn’t be any harm in doing extra work as well). If you can’t get access to any of the desired youth systems then maybe you could try an individual sport & look at what some of the top trainer have put online (it’s safer to knock the guy out rather than leave it to the judges even if it’s an individual sport… the “minimum” for any mastery is 10k hours of smart/intelligent practice/training).

Just an FYI, looking at MLS players instead of looking at data from top teams in the top European leagues is like the difference between average college scores vs average big money players in the NFL.

Go visit Liverpool, Real Madrid or Bayern Munich for example and prepare to have your mind blown about fitness technology, sports science and the power, speed and flexibility and endurance of soccer players.

“It doesn’t matter, since we know from research on the world’s best athletes in soccer none are outperforming the NFL athletes”

Find me one NFL sprinter that can make an 85 yard sprint in the 85th minute of a game in which he has not had a break except for one 15 minute halftime.

Find me an NFL sprinter that is put at wing back and is still keeping up with a soccer winger 20 minutes into the first half. Won’t happen.

Find me a NFL sprinter that can do half what 33 year old James Milner of Liverpool can do on the lactate test. You can’t.

Throw-ins definetly require you to lift your arms above your head. . .